The Wild Reed’s celebration of singer and actor Carl Anderson continues!

It’s actually a month-long celebration, as February is the month of both Carl’s birth (in 1945) and death (in 2004, at age 58).

In this fourth installment of The Wild Reed’s celebration of Carl, I share (with added images) a second excerpt from P. Djeli Clark’s insightful article, “My Own Personal Judas: Revisiting Jesus Christ Superstar.” (For the first excerpt, click here.)

This second excerpt focuses on Carl’s groundbreaking portrayal of Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Jesus, in the 1973 film adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice's celebrated rock opera.

As Clark notes: “In the end, we realize [Jesus Christ Superstar] isn’t really about Jesus. It’s about Judas. He is at the heart of the story. . . . It is the Passion of the Christ told from Judas’s perspective.”

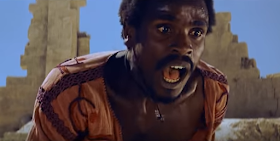

The film begins with Judas (Carl Anderson) breaking away from the others – a continual loner set apart; in some ways, much like Jesus.

Dressed in all red with his chest out, he sits atop a crag of rock surveying Jesus and the other disciples. And he isn’t happy. In a lengthy heartfelt soliloquy set to an ominous guitar string, he sings, My mind is clearer now . . . at last all too well, I can see where we all soon will be.

Jesus, he believes, has become reckless. He’s let all this “son of God” talk in the streets go to his head, and has put himself above his ideals. This, Judas laments, the Romans will not take lightly. Has Jesus forgotten how put down his people are by the Romans? Has he forgotten that at any moment the Empire could crush them, ending all the good they’ve accomplished?

Nor does Judas buy into the adoration of the crowds. Super stardom is fleeting, he says critically. You have set them all on fire, they think they’ve found the new Messiah. [But] they’ll hurt you when they find they’re wrong.

More than anything, Judas wants to be heard. He wants Jesus to listen, before it’s too late. The rest of the disciples are blind, he wails in disgust, “too much heaven on their minds.” He begs Jesus to abandon the super stardom and return to the simple days, for his sake, their sake and the sake of his nation. But Judas’s cries come from far away, atop a hilltop that sits as a metaphor for the distance that has grown up between the two men. And his words are wasted on the wind, never reaching his leader’s ears.

That scene alone establishes Anderson’s powerful delivery of a Judas we aren’t at all familiar with.

This Judas is tormented, angry and scornful – but with reason. He is disgusted not only with the popularity he sees swirling about Jesus, but that Jesus as well buys into it – even seems to promote it.

He questions the claims of divinity and sees Jesus instead as just a man, who in the end will lead both his followers and his people into a destructive confrontation with the Romans. After Jesus angrily attacks the money lenders in the temple (who sell everything from sex to military artillery) Judas comes to believe his leader has lost his mind.

Sitting in contemplation, he watches a set of Roman tanks. Seeming to visualize what could happen were the full might of the Roman Empire brought to bear upon them, he decides Jesus has to be stopped. What he does is for the good of all, not “blood money.” He only asks that for his actions, he not be “damned for all time.”

The climax in the conflict between both men is intense. When Jesus announces that one of his followers will betray him, a fed up Judas jumps up and declares “cut the dramatics you know very well who!” His anger has boiled over into seething hatred. “To think I’d admired you,” he spits. “Well now I despise you!”

Jesus angrily denounces him as a liar and tells him to go, not wanting to hear his excuses. For a brief moment, the two men clasp, and you remember they were once companions, a teacher and a pupil, comrades in a struggle. In both their faces there’s a moment of pain and regret. “Every time I look at you,” a frustrated Judas moans, “I don’t understand, why you let the things you did get so out of hand.” He flees to complete his deed. It’s the last time the two will speak.

. . . After bearing witness to Jesus being scourged, [Judas] runs back to the Pharisees to say this isn’t what he had agreed to. He cries out he would save Jesus if he could and seems overwrought by guilt. But the priests scornfully mock his remorse, reminding him of his willful role. In the end Judas realizes he’s been duped. But it’s not the Pharisees he blames. It’s not Jesus. It’s not even the Romans. In a final moment of clarity he looks up to the heavens, and he realizes that this was planned all along. Not by any men. This was planned by God. The one character who never makes an appearance in Jesus Christ Superstar but has been there all along.

God as ultimately responsible for this tragedy has been alluded to all along. Jesus says wearily earlier that the path he is on was started by God. Pontius Pilate calls Jesus a puppet. But who is pulling the strings?

“I’m sick!” Judas declares at his new-found revelation. “I’ve been used!” He runs about the desert aimlessly – as if trying to futilely escape the omnipresent Almighty. “You knew all the time,” he accuses. “God . . . I’ll never know why you chose me for YOUR crime!” Declaring God his murderer with his last breath, Judas hangs himself.

In a final sequence he returns as a spirit surrounded by what appear to be angels, or perhaps demons, and continues his philosophical questions while in other scenes Jesus is marched to his crucifixion. Who is Jesus? What has he sacrificed? Does he truly think he’s who the stories claim him to be? How do you separate the myth from the man? His questions go unanswered, echoed seemingly throughout eternity.

In the end, we realize this play isn’t really about Jesus. It’s about Judas. He is at the heart of the story. Though we get other perspectives, it is Judas we’re always drawn back to. It is the Passion of the Christ told from Judas’s perspective.

It ends much as we expect. But the motives and reasoning are given new depth and contours. Judas isn’t just the black betrayer in the Webber/Rice retelling, he is the black anti-hero. He is a two-dimensional popular villain now turned into a complex human being. Even if you don’t take his side in the end, you certainly understand it.

– P. Djeli Clark

Excerpted from "My Own Personal Judas:

Revisiting Jesus Christ Superstar"

Phenderson Djèlí Clark

April 18, 2014

Excerpted from "My Own Personal Judas:

Revisiting Jesus Christ Superstar"

Phenderson Djèlí Clark

April 18, 2014

Related Off-site Link:

Controversial Judas – Caroline Blyth (Auckland Theology & Religious Studies, December 20, 2016).

For more of Carl Anderson at The Wild Reed, see:

• Remembering and Celebrating Carl Anderson

• Carl Anderson: “Pure Quality”

• Carl Anderson's Judas in Jesus Christ Superstar: “The Gold Standard”

• Carl Anderson: “One of the Most Enjoyable Male Vocalists of His Era”

• With Love Inside

• Carl Anderson

• Acts of Love . . . Carl's and Mine

• Introducing . . . the Carl Anderson Appreciation Group

• Forbidden Lover

• Revisiting a Groovy Jesus (and a Dysfunctional Theology)

No comments:

Post a Comment