Joan Timmerman, one of my former theology professors at the College of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minnesota, contributed an insightful chapter to the 1994 anthology Sexuality and the Sacred: Sources for Theological Reflection (Nelson, James B., and Longfellow, Sandra P. (Eds.), Westminster/John Knox Press, Louisville, Kentucky) in which she explores this important though potentially controversial topic.

In her contribution entitled “The Sexuality of Jesus and the Human Vocation,” Timmerman observes that “the perfecting of human love has always been recognized as a goal of religion. It is markedly so when a religion, such as Christianity, affirms the vocation to love as the primary way of identifying with the creative, redemptive, and transformative activity of the divine. Theologies of Jesus as the Christ and the Christ as God would be expected to emphasize love as the path of imitation of Christ. What is surprising is that the love modeled by the archetypal figure of Christ should emphasize the commitments of parent and neighbor to the practical exclusion of conjugal, erotic love.”

Timmerman acknowledges that “such preferences can be explained historically,” yet she nevertheless maintains that “to appeal to the life of the historical Jesus to ground such preferences is mistaken.”

She then goes on to note that “the humanity of Jesus, like femininity and masculinity, is constructed by us as a cultural symbol. Those things that reflect the aspirations of our own ways of being human are included; those things which incorporate the confusions and conflicts we wish to reject, are left out. This need not, indeed could not, be a reflective, intentional process, but nonetheless there is evidence that the affirmation ‘Jesus Christ is truly human’ has shifting content. Its content depends on the adequacy of the anthropological assumptions that underlie its doctrinal formulation.”

Renowned theologian Edward Schillebeeckx, Timmerman reminds us, has written that our problem with developing an adequate Christology [i.e. a way of understanding and talking about Christ] is “not that we do not know enough about God, but that we do not know enough about what it means to be human.”

Timmerman rightly observes that when the classical descriptions of Jesus’ manhood were formulated, “it was in line with the conventional dualistic model,” one in which it was “unthinkable to include in normative humanity those things associated with women, connectedness, vulnerability, immersion in nature.”

Today, of course, any formulation about what it means to be human which does not take into account the experience of women is, says Timmerman, “simply wrong,” as it “represents not the normatively human but the male; it is vitiated because it is the partial pretending to be the universal.”

Timmerman also highlights the problem of anachronism, noting that “each age attempts to read its own preferred values into the image of the God-man.”

Accordingly, she observes that “Jesus has been cast as one of the desert hermits, as a royal ruler of the imperial kingdom, as a bishop shepherding the flock, as a divine physician healing plague-stricken victims, as a reformer cleansing old institutional forms, as the divine teacher of conventional morality, as the liberator, urging people to claim their intrinsic dignity, and of course as the supreme celibate who, free of all concupiscence, was never even tempted to intercourse with women.”

All of this, says Timmerman, is appropriate to a mythic, paradigmatic figure. “Only when formulated as if it were to be taken as revelation of the full and literal God-willed way of being human, and, as such, becomes the object of faith, only then does it become oppressive. The mythic becomes pernicious when it is understood and applied literally.”

“The doctrine of faith, the formulated content of revelation,” Timmerman reminds us, “is that Christ is fully human and fully divine.” She goes on to note that “the belief statements, written or unwritten, regarding what kind of sexual fulfillment full humanity entailed in Jesus, or in us, are subject to change. They are formulated according to historical and cultural insights and limitations, and to pretend otherwise is to mistake the words of men for the Word of God. Anyone sensitive to his/her own life knows that the experiences of loneliness, doubt, powerlessness, and fear have a different character when they are filtered through adult sexual awareness. To exclude on principle both this pleasure and this pain from Jesus’ human life seems an impoverishment indeed. The greater impoverishment, of course, is ours.”

Timmerman also reminds us that “the precise function of the Holy Sprit, given by the risen Jesus to the community he left, was to lead that community continuously into deeper and fuller knowledge of Christ.”

With regard speaking to the churches about the sexuality of Jesus, Timmerman observes that the Spirit has “only just begun.” She suggests this is because “our acceptance of [Jesus’] sexuality [is] conditional upon our esteem for our own,” just as “our appreciation of his humanity is dependent on our insight into our own.”

“The incarnation,” says Timmerman, “in a real sense, is not complete until the community of people discovers God disclosed in their own humanity; just so, an element of Christology is lacking until we can allow ourselves to formulate images of Jesus entering as deeply into the passion of sexuality as we have done regarding the passion of his suffering.”

To read a 1999 lecture by Joan Timmerman on the topic of “Sexuality and Spirituality,” click here.

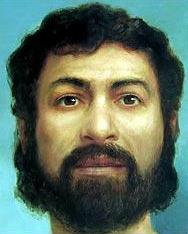

Image 1: The face of a first-century Semitic man, rendered by the contemporary artist Donato Giancola. This image was featured in a 2004 New York Times article entitled “What Did Jesus Really Look Like?”

Image 2: Michael Bayly.

No comments:

Post a Comment