Depictions of the "strange man of the Oglalas"

in art, film, and sculpture.

Today marks the 137th anniversary of the murder of the Oglala Lakota warrior and mystic Tȟašúŋke Witkó ('His-Horse-Is-Crazy' or 'His-Horse-Is-Spirited') generally known as Crazy Horse (ca. 1840 – 1877).

I commemorate the life and journey of Crazy Horse today by sharing various depictions of him in art, film, and sculpture.

Right: Standing next to the stone cairn that marks the spot at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, where Crazy Horse was fatally bayoneted on September 5, 1877. For more images and commentary on my 2013 visit to Fort Robinson, click here.

As I've mentioned in a previous Wild Reed post, my interest in Crazy Horse has little to do with the warrior aspect of his story but rather with what writer Ian Frazier says is the "magic of Crazy Horse . . . how unique and brave and chivalrous and unpredictable and uncaught he was."

In Frazier's opinion, Crazy Horse was great because he "remained himself from the moment of his birth to the moment he died. . . [H]e knew exactly where he wanted to live, and never left." Furthermore, writes Frazier, Crazy Horse's "dislike of the oncoming civilization was prophetic. He never met the President, never rode on a train, slept in a boarding house, or ate at a table. And, unlike many people all over the world, when he met white men he was not diminished by the encounter."

Known by the Oglala Lakotas as "our strange man," Crazy Horse was somewhat of a loner; an outlier dedicated to the welfare of his people but indifferent to tribal norms. He ignored, for instance, the sundance and, writes Larry McMurtry, "didn't bother with any of the ordeals of purification that many young Sioux [or Lakota] men underwent." Orthodoxy was never Crazy Horse's way – yet another reason, no doubt, for my admiration and interest in his life and story. I also appreciate and resonate with author Chris Hedges' observation that Crazy Horse's "ferocity of spirit remains a guiding light for all who seek lives of defiance."

Crazy Horse never allowed himself to be photographed. Over the years, however, numerous photographic images have surfaced purporting to show the 'strange man of the Oglalas.' A number of these images are on display at the Crazy Horse Museum at Thunderhead Mountain, South Dakota (below).

It should be noted that although Crazy Horse was a skilled warrior, his humility ensured that he never wore a war bonnet, as two of the figures are depicted wearing in the display of photographs above. Of these photographs, perhaps the most controversial is the one at bottom right. For a discussion on this particular image and how it was ultimately deemed not to be a photograph of Crazy Horse, click here.

Left: A 1934 sketch of Crazy Horse made by a Mormon missionary after interviewing Crazy Horse's sister, who claimed the depiction was accurate. The drawing belongs to Crazy Horse's family, and has been publicly shown only once, on the PBS program History Detectives.

Right: A black-and-white image of an ink and watercolor portrait of Crazy Horse painted around 1940 by Lakota artist Andrew Standing Soldier. According to the Lakota Country Times, "the artist had gained a reputation for his accurate portrayals of Lakota life in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as historic events. The painting was based on descriptions given to the artist by Crazy Horse's relatives and close friends, who reportedly pronounced it an excellent likeness." The original of this painting is in the Sheridan County Historical Museum in Rushville, Nebraska.

Above: Crazy Horse’s fatal stabbing at Camp Robinson on September 5, 1877, recorded by the Oglala artist Amos Bad Heart Bull. According to Thomas Powers in The Killing of Crazy Horse (2010), "One fact was remembered with special clarity by almost every witness – Little Big Man’s effort to hold Crazy Horse as he struggled to escape."

Powers' The Killing of Crazy Horse is the most extensively researched book available on the death of Crazy Horse. Following is an excerpt from Susan Salter Reynolds' Los Angeles Times review of Powers' book.

History and story, myth and legend, primary and secondary sources form a thicket around Crazy Horse's death. He was certainly a threat to the U.S. Army. For 20 of his approximately 33 years, he fought U.S. government efforts to encroach on native land, particularly in the gold-rich Black Hills of South Dakota. He was a significant leader in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 and has been credited by many with the Native American victory in that engagement and the death of Gen. George Armstrong Custer. This was only one of the many battles in Crazy Horse's life. Stories of his bravery, told in other tribes and reported in various newspapers, took on a mystical, legendary quality even in his lifetime. These stories have grown even more vivid with time — for many, Crazy Horse has been the human embodiment of the last stand in the Native American way of life. Treaties came and went, but Crazy Horse represented something different: Native American power.

. . . The death of Crazy Horse seems a hollow, pointless betrayal, premeditated by U.S. officials. Although many accounts recorded by soldiers claim that Crazy Horse backed into the bayonet of a soldier ushering him toward the jailhouse, there can be no doubt after Powers' telling that he was murdered and that the murder was planned.

Above: The killing of Crazy Horse as depicted by Joe Servello in William Kotzwinkle's children's book The Return of Crazy Horse.

Above: Amos Bad Heart Bull's depiction of the June 25-26, 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn. Crazy Horse is pictured center.

Above: The Battle of the Little Big Horn as illustrated by S.D. Nelson in Joseph Bruchac's children's book Crazy Horse's Vision. Writes Nelson:

As a member of the Standing Rock Sioux [or Lakota] tribe in the Dakotas, my painting has been influenced by the traditional ledger book style of my ancestors. The picture on the endpapers of this book [detail above] was painted in the traditional ledger book style of the

plains Indians, which include the Lakota people. It shows the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the crowning achievement of the Lakota chief, Crazy Horse.

What is the ledger book style and where did it come from? During the last part of the nineteenth century, Native peoples were forced onto reservations by the United States government. Some of the strongest resistance to this was among the Plains Indians. As a result, many of their leaders were put in prison, and hundreds of children were sent east to boarding schools to be "civilized." During this time, some Indians were given ledger books in which to draw. These books had lined pages and were intended for bookkeeping. Artists used pencils, pens, and watercolors on the ledger book pages to create bold images of their vanishing culture. Their work was distinguished by outlined two dimensional figures and indistinct facial expressions.

Continues S.D. Nelson in the "Illustrator's Note" of Crazy Horse's Vision:

For the Lakota people, colors have special meanings. For example, red represents the east where each day begins with the rising of the sun. Yellow represents the south, summer, and where things grow. I painted Crazy Horse blue because blue represents the sky and a connection with the spirit world.

I included other traditional symbols in my art for this book. Plains Indians often painted themselves, their horses, and their tipis. They believed that doing so gave them special spiritual powers. Warriors used images of lightning bolts and hail spots to represent the awesome power of a thunderstorm. Images of lizards and dragonflies represented speed and elusiveness.

As a young boy, Crazy Horse, then known as Curly, embarked on a vision quest. As was his way, however, he ignored the rituals and procedures of purification that would normally precede such a quest. Yet he nevertheless experienced a vision. Following is how Russell Freedman describes this vision in his book The Life and Death of Crazy Horse. This excerpt is accompanied by S.D. Nelson's cover illustration for Joseph Bruchac's Crazy Horse's Vision (left) and a depiction of Crazy Horse's vision by artist Roy La Plante from the cover of Win Blevins' Stone Song: A Novel of the Life of Crazy Horse (below).

For two days [Curly] remained on the hilltop without eating, fighting off sleep, his eyes like burning holes in his head, his mouth as dry as the sandhills around him. When he could barely keep his eyes open, he would get up and walk around and sing to himself. He grew weak and faint, but no vision came to him. Finally, on the third day, feeling unworthy of a vision, he started unsteadily down the hill to the lake where he had left his hobbled pony.

His head was spinning, his stomach churning. The earth seemed to be shaking around him. He reached out to steady himself against a tree. Then – as he himself would later describe it – he saw his horse coming toward him from the lake, holding his head high, moving his legs freely. He was carrying a rider, a man with long brown hair hanging loosely below his waist. The horse kept changing colors. It seemed to be floating, floating above the ground, and the man sitting on the horse seemed to be floating, too.

The rider's face was unpainted. He had a hawk's feather in his hair and a small brown stone tied behind one ear. He spoke no sounds, but Curly heard him even so. Nothing he had ever seen with his eyes was as clear and bright as the vision that appeared to him now. And no words he had ever heard with his ears were like the words he seemed to be hearing.

The rider let him know that he must never wear a war bonnet. He must never paint his horse or tie up its tail before going into battle. Instead, he should sprinkle his horse with dust, then rub some dust over his own hair and body. And after a battle, he must never take anything for himself.

All the while the horse and rider kept moving toward him. They seemed to be surrounded by a shadowy enemy. Arrows and bullets were streaking toward the long-haired rider but fell away without touching him. Then a crowd of people appeared, the rider's own people, it seemed, clutching at his arms, trying to hold him back, but he rode right through them, shaking them off. A fierce storm came up, but the man kept riding. A few hail spots appeared on his body, and a little zigzag streak of lightning on his cheek. The storm faded. A small red-backed hawk flew screaming over the man's head. Still the people grabbed at him, making a great noise, pressing close around him, grabbing, grabbing. But he kept riding.

The vision faded. . . .

Above: Detail of a depiction of Crazy Horse by Kenneth Ferguson (2006).

The Death of Crazy Horse: A Tragic Episode in Lakota History is a compilation of eyewitness accounts of the last days of Crazy Horse. Edited by Richard G Hardorff, the book contains the "narrative" of Susan Bordeaux Bettelyoun, born near Fort Laramie in 1857. In the 1930s Bettelyoun wrote a number of manuscripts, one of which is known as the Crazy Horse manuscript. Following is an excerpt.

My husband, Chas Tackett, was a scout, but when he was not on duty, he clerked in Jewett's store, and had waited on Crazy Horse. My mother-in-law and I drove up to the store when Crazy Horse was there; she pointed him out to me. He was a very handsome young man of about thirty-six years or so. He was not dark; he had hazel eyes, [and] nice, long light-brown hair. His braids were wrapped in fur. He was partly wrapped in a broad-cloth blanket; his leggings were also navy-blue broad-cloth, his moccasins were beaded. He was above the medium height and was slender.

Above: Detail of the cover illustration by Ed Lindlof of the 1992 edition of Crazy Horse: The Strange Man of the Oglalas by Mari Sandoz.

Above: "Crazy Horse" by Dan Nance.

As I mentioned earlier in this post, although I certainly respect Crazy Horse's courage on the battlefield, the warrior aspect of his life and journey isn't the primary focus of my interest in him. I also think it's important to note Paula Gunn Allen's perspective, one which she articulates in her insightful book The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions.

As long as [Indian people] are seen [solely] as braves and warriors the fiction that they were conquered in a fair and just war will be upheld. It is in the interest of the United States – along with the other political entities in the western hemisphere to maintain that foolish and tragic deception, and thus the focus has long been on Indian as noble or savage warrior who, as it happens, lost the war to superior military competence. The truth is more compelling: the tribes did not fight off the invaders to any great extent. Generally they gave way to them; generally they fed and clothed and doctored them; generally they shared their knowledge about everything from how to plant corn and tobacco to how to treat polio victims to how to cross the continent with them. Generally, Chief Joseph, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and the rest are historical anomalies. Generally, according to D'Arcy McNickle, the Indian historian, anthropologist, and novelist, at least 70 percent of the tribes were pacifist, and the tribes that lived in peacefulness as a way of life were always women-centered, always gynecentric, always agricultural, always "sedentary," and always the children of egalitarian, peace-minded, ritual and dream/vision-centered female gods. The people conquered in the invasion of the Americas by Europe were women-focused people.

. . . [T]he traditions of the [female energy] have, since time immemorial, been centered on continuance, just as those of the [male energy] have been centered on transitoriness. The most frequently occurring male themes and symbols from the oral tradition have been feathers, smoke, lightning bolts (sheet lightning is female), risk, and wandering. These symbols are all related in some way to the idea of the transitoriness of life and its wonders. The Kiowa death song (a male tradition that was widespread among Plains tribes) says, "I die, but you live forever; beautiful Earth you alone remain; wonderful Earth, you remain forever," telling the difference in the two traditions, male and female.

Above: "Crazy Horse" by John Nieto.

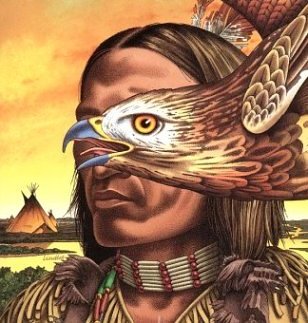

Above: "Vision of Crazy Horse." I found this image here on the Gallery in Mount Shasta website. It's unclear who the artist of this work is. Yet judging from artwork on the site that is of a similar style, I believe the artist is David Joaquin.

Above and below: Crazy Horse as depicted by artist Joe Servello in William Kotzwinkle's children's book The Return of Crazy Horse, described by Ruth Ziolkowski, wife of the creator of the Crazy Horse Memorial, as "one of the first books about Crazy Horse and the memorial for youngsters."

Above: Detail of the cover illustration by William Reusswig of the 1954 children's book The Story of Crazy Horse by Enid Lamonte Meadowcroft.

Above: A depiction of Crazy Horse from the My Hero Project website. It accompanies a piece written by "Courtney from California," part of which reads:

What makes Crazy Horse a hero to me is that he was fearless and wanted to save his land and people from those who were trying to take it over. He didn't just sit around and let them kill his people and take his land, but he fought back, and he kept fighting up until the day he died. He did not succeed in [keeping] his land, but at least he tried, and made a difference. His people will always remember him as a strong, kind, and brave hero.

Above: A painting of Crazy Horse by John Beheler, former director of the Dakota Indian Foundation.

Above: Hollywood actor Victor Mature in the title role of the 1955 film Chief Crazy Horse.

Writes Chad Coppess at Cinema South Dakota:

In 1955 Universal International Pictures released Chief Crazy Horse, which supposedly depicts the life of the famed Lakota warrior. It was filmed in South Dakota's Black Hills and Badlands. Unfortunately, this is one of those cases where Hollywood played loose and fast with the facts. Scriptwriting aside, casting and costuming leave a lot to be desired in the accuracy department. Victor Mature plays the title role. His Italian ancestry and some heavy makeup apparently made him perfect for the character and entitled to wear a ridiculous set of red painted feathers on his forehead.

Above and right: Michael Dante as Crazy Horse in the short-lived 1967 western television series Custer (also known as The Legend of Custer).

Notes Wikipedia:

The ABC network's Custer faced competition from NBC's long-running 90-minute western The Virginian starring James Drury and Doug McClure and CBS's Lost in Space starring Guy Williams, June Lockhart, and Mark Goddard.

Wayne Maunder was twenty-eight when he was cast as the 28-year-old Custer. The show was canceled due to wide protest of Native American tribes throughout the United States.

Above: Rodney A. Grant as Crazy Horse in Son of the Morning Star, a 1991 miniseries about George Armstrong Custer.

In his book The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History, Joseph M. Marshall III notes the following about Son of the Morning Star and a number of other film and TV projects that depict Crazy Horse.

In a 1991 made-for-television miniseries (about Custer), [Crazy Horse] was a moody, reticent pedestrian (literally). A feature film the same year in which he shared equal billing with Custer attempted the "untold story" approach, but it went awry soon after the opening credits. Between 1955 and 1996 he has appeared as a background or minor character in several westerns, and once as an insect-eating captive in a western television series about Custer that lasted only slightly longer than the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Above and left: As I've noted previously, my introduction to the 'strange man of the Oglalas' was through John Irvin's 1996 telemovie Crazy Horse, starring Michael Greyeyes.

Filmed on location in South Dakota and Nebraska, the film has been described as a "gripping story with a fine cast" and praised for its attention to detail. As has been noted, in The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History, historian and author Joseph M. Marshall is critical of movie portrayals of Crazy Horse. Yet he concedes that Irvins' film "came the closest" in credibly portraying Crazy Horse's life and story.

Right and below: Michael Greyeyes as Crazy Horse in John Irvins' 1997 film Crazy Horse, a work that remains inexplicably unavailable on DVD.

Left: Jay Red Hawk as Crazy Horse in Oliver Tuthill's 2010 feature-length documentary, Questions for Crazy Horse: Hypothetical Conversations with the Strange Warrior of the Oglala Lakota.

Notes the film's website: "This film takes an introspective look into how American Indians perceive [Crazy Horse] and what questions they would have for him concerning contemporary problems if he were alive today." Elsewhere, the film is described as "an imaginative, fearless attempt to help bridge the gap between myth and modern Indian life."

Above: A bronze sculpture of Crazy Horse by Sunti Pichetchaiyakul, part of the artist's Native American Chiefs Collection.

On Sunti Pichetchaiyakul's website the following is noted:

Sunti was very fortunate to work with one of Crazy Horse’s living relatives, Donovin Sprague, who provided Sunti with a family sketch of the warrior and shared with Sunti the oral history of the Lakotas, describing Crazy Horse’s appearance. Legend tells that Crazy Horse had a light complexion and light hair, which he wore long with either one or two red tail hawk feathers, or an eagle feather. Crazy Horse did not wear a war bonnet or many accessories, however Crazy Horse brushed himself with soil and painted small white circles on his body as war paint. He was also given a stone by a medicine man that would protect Crazy Horse during battle. The warrior strapped this stone behind his ear and it is told that the stone would heat up when the enemy was near, alerting him of danger. Yet Crazy Horse’s most prominent feature is the 2-3 inch vertical scar on his left cheek in which a bullet entered his cheek bone and exited out of his lower jaw. While there is a lot of mystery as to whether or not the scar was on the right side of Crazy Horse’s face and whether the bullet actually entered under his jaw and exited out of his cheekbone, Sunti was determined to depict Crazy Horse in the way that he is remembered by his people, which is also, perhaps, most historically accurate.

Above: "Crazy Horse" by Batguy.

Above: Another sculpture by Sunti Pichetchaiyakul depicting Crazy Horse. This one is entitled "Crazy Horse: He Rides His Horse Like the Eagle Rides the Wind." It is based on John Clymer’s painting, "Crazy Horse" (detail at left).

Above: "Crazy Horse" by Bill Churchill.

Above: The Crazy Horse Memorial, an ongoing project at Thunderhead Mountain in Custer County, South Dakota. The mountain carving (referred to as the monument component of the project) was designed by the Polish-American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski.

As I mention in a previous post, I think it's unfortunate that this particular depiction of Crazy Horse is so unnaturally rigid. Compare it, for instance, to those of sculptors Sunti Pichetchaiyakul and Bill Churchhill, highlighted above. Like these sculptors, I picture Crazy Horse galloping across the plains, his body loose and fluid, his head down low to that of his horse's. I would have loved to have seen a sense of this energy and movement reflected in Ziolkowski's work. I also have an issue with the monument's depiction of Crazy Horse pointing his finger towards his ancestral home of the Great Plains. This is because in many Native American cultures using the index finger to point at people or objects is considered rude. Perhaps this issue will be addressed when the hand of Ziolkowski's monumental Crazy Horse sculpture is completed.

Notes Wikipedia about the Crazy Horse Memorial:

The memorial was commissioned by Henry Standing Bear, a Lakota elder, to be sculpted by Korczak Ziolkowski. It is operated by the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation, a private non-profit organization. The memorial consists of the mountain carving (monument), the Indian Museum of North America, and the Native American Cultural Center. The monument is being carved out of Thunderhead Mountain on land considered sacred by some Oglala Lakota, between Custer and Hill City, roughly 17 miles from Mount Rushmore. The sculpture's final dimensions are planned to be 641 feet (195 m) wide and 563 feet (172 m) high. The head of Crazy Horse will be 87 feet (27 m) high; by comparison, the heads of the four U.S. Presidents at Mount Rushmore are each 60 feet (18 m) high.

The monument has been in progress since 1948 and is far from completion. If completed, it may become the world's largest sculpture.

Left: Standing beneath the Crazy Horse monument, June 10, 2013. For more images and commentary on my visit to Thunderhead Mountain and the Crazy Horse Memorial, click here.

Above: Detail of the model for the Crazy Horse Memorial.

Above: "Crazy Horse" by redrab8t. This drawing is actually a rendering of the opening image of this post, which in turn serves as the haunting cover illustration of Russell Freedman's book The Life and Death of Crazy Horse. Nowhere in Freedman's book is the artist of this cover illustration credited.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• Crazy Horse: "Strange Man" of the Great Plains

• Pahá Sápa Bound

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 1: The Journey Begins

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 2: The Badlands

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 3: Camp Life

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 4: "The Heart of Everything That Is"

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 5: "I Will Return to You in the Stone"

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 6: Hot Springs, South Dakota

• Pahá Sápa Adventure – Part 7: Fort Robinson

• Michael Greyeyes on Temperance as a Philosophy for Surviving

• Something Special for Indigenous Peoples Day

• North America: Perhaps Once the "Queerest Continent on the Planet"

• "Something Sacred Dwells There"

Related Off-site Link:

Time to Get Crazy – Chris Hedges (TruthDig, July 2, 2012).

Recommended Books:

The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History – Joseph M. Marshall III (Penguin Books, 2005).

Crazy Horse: A Life – Larry McMurtry (Penguin Books, 1999).

Crazy Horse: Strange Man of the Oglalas (Third Edition) – Mari Sandoz (Bison Books, 2008).

Crazy Horse: A Dakota Life – Kingsley M. Bray (University of Oklahoma Press, 2008).

Crazy Horse: A Photographic Biography – Bill and Jan Moeller (Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2000).

The Life and Death of Crazy Horse – Russell Freedman (Holiday House, 1996).

Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors – Stephen E. Ambrose (Anchor, 1996).

Crazy Horse's Vision – Joseph Bruchac (Lee and Low Books, 2006).

The Killing of Crazy Horse – Thomas Powers (2010).

The Death of Crazy Horse: A Tragic Episode in Lakota History – Richard G. Hardorff (Bison Books, 2001).

Stone Song: A Novel of the Life of Crazy Horse – Win Blevins (Forge, 1995).

Thank you very much for this richness of research, and selection of art dealing with Crazy Horse.

ReplyDeleteA true hero of the Sioux, and a warrior to fear.

Thank you, very inspirational. Annemarie Slee, the Netherlands, Europe

ReplyDeleteMuito interessante este blogue. Parabéns por mostrar ao mundo traços da vida de “Cavalo Doido”. O Zé Mancambira já me havia perguntado por ele, se eu sabia alguma coisa. Infelizmente, na época pouco sabia, hoje, com suas informações, seu muito mais.

ReplyDelete