Recently I was talking with my friend Paula about Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows. Paula asked if I remember that part of the story where Mole and Rat encounter Pan. It's one of her favorite chapters of the book, in large part because of its strange and haunting beauty.

To be honest, I only have a vague recollection of it. But, then again, even though I read The Wind in the Willows as a child, it could well be that I never actually encountered this particular part. How could this be?, you may ask. Well, according to Jamie Andrews of the British Library, the chapter in question, "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn," is "normally dropped because it jars, seems so strange compared to all the others and, to some, is vaguely homo-erotic."

Grahame, however, says Andrews, "thought it essential."

So what's this "strange" chapter of The Wind in the Willows all about? Well, it starts with Rat and Mole searching the river for a lost baby otter named Portly. Soon, however, they find themselves drawn by a distant haunting melody to a small island:

Slowly, but with no doubt or hesitation whatever, and in something of a solemn expectancy, the two animals passed through the broken tumultuous water and moored their boat at the flowery margin of the island. In silence they landed, and pushed through the blossom and scented herbage and undergrowth that led up to the level ground, till they stood on a little lawn of a marvellous green, set round with Nature’s own orchard-trees — crab-apple, wild cherry, and sloe.

"This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me," whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. "Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!"

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror — indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy — but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty he turned to look for his friend, and saw him at his side cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew.

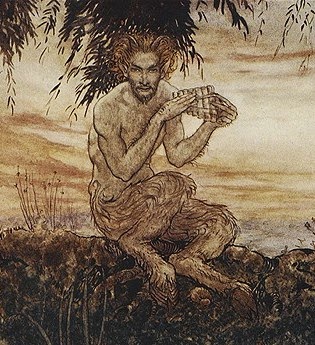

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible color, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

"Rat!" he found breath to whisper, shaking. "Are you afraid?"

"Afraid?" murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. "Afraid! Of him? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!"

The "unutterable love" that radiates from Rat reminds me of the mystic's response to God as "the Beloved." It's a response found within a range of mystical traditions – Christian, Sufi, Jewish – and one that often has erotic, including homo-erotic, overtones. I'm drawn to this type of universality, though to be sure it's a catholicity of religion rather than of church.

Grahame's depiction of his characters' encountering of Pan also calls to mind theologian Paul Collins' writing on the Latin word terribilis, which he says points to the awe and trepidation required of one who is in the presence of God. It's a word that emphasizes the fact that God "is wholly other, not anthropomorphic, not domesticated. God is ultimately a mysterium in the sense that the divine is a phenomenon to be explored, not a reality to be possessed or defined."

This sacred mystery goes by many names. In his 2012 article in Credo, Matthew Claridge notes that Grahame's description of Pan shares similarities with descriptions of Christ. He writes, for example, that:

There is a great deal here that a biblical Christian should appreciate and even accept—Christ is indeed the Lord of the Jubilee, the “Friend and Helper” of little creatures such as sparrows, flowers and frail men, the Lion of Judah and Lamb that was slain. There is definite truth in the fact that when we finally behold Christ, his blinding beauty, glory, and irresistible power will instantly transform and beautify our souls, purging it of all lesser loves (Rom. 8.1; 1Jn. 3.1ff). Indeed, like Pan’s song which is carried along the Wind, a song that creates and upholds the world, so we live in a world infused with the Spirit of Christ performing the same unconscious, untraceable functions (Jn. 3.8; 16.7ff.).

Jason Pitzl-Waters, a modern-day pagan, believes that Grahame’s portrayal of Pan was "instrumental in the slow establishment of this horned god (and other horned gods to come) in the minds and hearts of his British readers." Continues Pitzl-Waters:

[Grahame's] Pan, like the Pan of fellow authors Maurice Hewlett, Eden Phillpotts, and Lord Dunsany was a sort of “Green Jesus,” a savior of the natural world. A figure who would save humanity from destructive progress, and free them from outdated and restrictive moral codes.

All of which reminds me of Fran Recacha's painting entitled "Pan and the Defense of the Last Tree." It's a powerful, thought-provoking work of art, and one that can be viewed by clicking here.

Related Off-site Links:

Mole and Rat Meet the Horned God Pan in British Library Summer Exhibition – Mark Brown (The Guardian, February 28, 2012).

Beyond the Wild Wood – Alan Jacobs (First Things, October 2009).

Christ and Pan in The Wind in the Willows – Matthew Claridge (Credo Magazine, July 6, 2012).

The Wind in The Willows and the Voice of Old Gods – Mark Chadbourne (August 23, 2013).

Piper at the Gates of Dawn: Pan, Kenneth Grahame and Wind in the Willows – Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog (April 6, 2015).

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

Pan's Labyrinth: Critiquing the Cult of Unquestioning Obedience

"More Lovely Than the Dawn": God as Divine Lover

"Joined at the Heart": Robert Thompson on Christianity and Sufism

The Inherent Sensuality of Roman Catholicism

Never Say It Is Not God

It Happens All the Time in Heaven

Image 1: Arthur Rackham's illustration of Pan from The Wind in the Willows.

Image 2: Michael Hague.

Image 3: Artist unknown.

Thanks for the Piper at the Gates of Dawn and the Defense of the Last Tree, Michael. My mother read us this book. You always know Pan is around when you hear the music of the wind through the wild reeds. Eros is sacramental, isn't it?

ReplyDeleteThat is beautiful Michael - thanks for calling my attention to it. It's delightful.

ReplyDeleteGlad you liked it, Terry!

ReplyDelete"The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" was the name of Pink Floyd's first album. It is said that the book "Wind In The Willows" was a favorite of Syd Barrett who was their principle songwriter at the time.

ReplyDelete