Conservatives and reactionaries of various stripes have been quick to dismiss and condemn Mexican director Guillermo del Toro’s film Pan’s Labyrinth (El Laberinto del Fauno) as “leftist political fantasy.”

Yet perhaps what is pissing them off most about the film has been left unsaid: its critique of unquestioning obedience.

I’d be the first to admit that I have a hard time with violence in films. And Pan’s Labyrinth has a number of disturbingly violent scenes. Yet unlike, say, the average Mel Gibson film, including The Passion of the Christ, the scenes of violence in Pan’s Labyrinth are not gratuitously unending. Rather, they’re brief and serve a purpose; namely, to illustrate the cruel and violent nature of the film’s Captain Vidal and, by extension, the fascist regime of Spain’s General Francisco Franco.

Pan’s Labyrinth opens in 1944. The fascists, under Franco, have largely won the Spanish Civil War, though resistance remains. In a recent interview, the film’s director, Guillermo del Toro, observes that, “Most people think that the Civil War ended in 1939, but in reality the leader of the [rebel] group that was called the Maquis, was executed . . . in the 1960s. The resistance in Spain was very brave, and it held from 1939 into the [time of the film] because they were hoping that the Allies would turn around and help them after World War II. The resistance in Spain was actively involved in, for example, sabotaging the shipping of tungsten from the mines in Galicia to Germany to build the Panzer tanks. So they were really actively fighting the Nazis, and they were evidently rewarded with absolute indifference after the war.”

By 1944 the fascists had claimed victory, and, in the opening sequences of Pan’s Labyrinth, two spoils of this victory – the beautiful and delicate Carmen (Ariadna Gil) and her young daughter Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) – are being brought to Navarra in the north of Spain where Captain Vidal (Sergi Lopez) and his men have set up base in a rambling old house. It is from here that the captain is determined to rout out from the surrounding hills the remaining rebel forces.

Carmen is the captain’s new wife. She is also heavily pregnant with their child. Ofelia is Carmen’s daughter from a previous marriage. Though her mother implores her to call Captain Vidal “father,” Ofelia remains loyal to her real father who worked as a tailor before his death.

Vidal is using Carmen. Her sole purpose seems to be to provide a son for him. Ignoring the advise of Doctor Ferreiro (Alex Angulo), Vidal has had Carmen brought via a rough forest track to his isolated and potentially dangerous outpost on the edge of rebel territory. Once at Navarra, Carmen’s health takes a turn for the worse. “If there is a choice,” Vidal tells Doctor Ferreiro, “save the baby.” Not surprisingly, Vidal has little if any patience or concern for Ofelia.

Paul Bond notes that, “Vidal . . . a stickler for punctuality and military formality, wants his son to be born in Franco’s ‘new Spain’ – which he will create by brute force if necessary. ‘The war is over and we won,’ he says, and he is determined to kill all resisters to prove it. . . . [His] sadistic repression is brought out in some terrible and violent sequences, such as [his] beating a poacher to death with a bottle.”

Soon after her arrival to the violent and sadistic environment of her step-father, Ofelia finds herself caught up in a fantasy world – centered on a vast and crumbling labyrinth in which a faun tells her that she is the long lost princess of another realm, a realm free of lies and violence. In order to return to her rightful home and family, Ofelia must complete a number of tasks outlined by the faun.

That these tasks, along with the frightening creatures she encounters while completing them, mirror the events unfolding in the world beyond the labyrinth, suggest that Ofelia’s adventures are her way of attempting to process and make sense of the brutality and insanity in the “real world” – a state of affairs which her innocent and childlike spirit simply cannot comprehend.

Spain’s brutal reality

Yet as Paul Bond points out: “Because every twist and development of Ofelia’s fantasy world is intimately bound up with and shaped by her experiences, she can never escape life’s horrors. Her fantasy world begins to mirror Spain’s brutal reality. The characters she has created such as the Faun, played by Doug Jones, become ever more sinister. Ofelia confronts monsters, but is unable to triumph over them unequivocally. Reflecting her feelings of impotence, her fantasy tasks are dangerously beyond her. In the hall of the pale man, a chillingly vile Jones again, she barely escapes with her life. And eventually the two worlds meet.”

Before this fateful meeting, the two worlds, says critic David D’Arcy, are rendered thus: “the angular, upright realm of domination, and the dark, curved sanctuaries of the spirit.”

D’Arcy also asks us to “bear in mind that the Spanish Civil War was the war the Fascists won, in spite of lingering resistance that continued for years. It inspired Guernica, Picasso’s huge painting of a nightmarish bombing of a Basque town. This was war against civilians, in which entire cities were bombed.”

“It was also the first modern media war,” continues D’Arcy, “with aerial newsreel footage of battles that were proving grounds for new weapons, post-mortem photographs of dead babies on the covers of newspapers and global fundraising campaigns promoted on posters that were surreal collages.”

Del Toro’s film clearly seeks in many ways to reflect the grotesque style of Picasso. Yet in an interview with D’Arcy, del Toro also notes that he was inspired by Symbolist paintings of the late 19th century.

The film is also dedicated to the act of remembering, of not forgetting the past. This is especially significant given the fact that there remains – even in today’s socialist Spain – elements that seek to gloss over certain aspects of the country’s fascist history.

Says Bond in his review of Pan’s Labyrinth for the World Socialist Website, “Every detail here is aimed at historical memory, from Ofelia’s refusal to forget her real father to comments about Vidal’s father serving in Morocco, the scene of some of the Spanish military’s worst atrocities.”

An “unfair swipe” at the Catholic Church?

Of course, such insights and connections are lost on the many conservative American commentators and reviewers – some of whom not only dismiss the film as “socialist propaganda,” and “leftist political fantasy,” but even imply that Franco was some kind of Catholic conqueror of Communism. Not surprisingly, these and other conservative-leaning pundits, such as Catholic film critic Barbara Nicolosi, are miffed at what they see as del Toro’s “unfair swipe at the Church.”

Unfair? It’s a historical fact that powerful elements within the Catholic Church supported Franco’s fascist regime. As Bond observes, “del Toro’s apparently sincere use of redemptive imagery stands in stark contrast to the actual role of the Catholic Church in Spain. But he does indicate this with the presence of the priest at Vidal’s dinner, offering ecumenical support for the fascist persecution of the resistance.” It must also be noted that the Church benefited handsomely from this “support.”

As the Library of Congress notes: “Roman Catholicism [during the Franco years] was the only religion to have legal status; other worship services could not be advertised, and only the Roman Catholic Church could own property or publish books. The government not only continued to pay priests’ salaries and to subsidize the church, but it also assisted in the reconstruction of church buildings damaged by the war. Laws were passed abolishing divorce and banning the sale of contraceptives. Catholic religious instruction was mandatory, even in public schools. Franco secured in return the right to name Roman Catholic bishops in Spain, as well as veto power over appointments of clergy down to the parish priest level. In 1953 this close cooperation was formalized in a new Concordat with the Vatican that granted the church an extraordinary set of privileges: mandatory canonical marriages for all Catholics; exemption from government taxation; subsidies for new building construction; censorship of materials the church deemed offensive; the right to establish universities, to operate radio stations, and to publish newspapers and magazines; protection from police intrusion into church properties; and exemption of clergy from military service.”

“The proclamation of the Second Vatican Council in favor of the separation of church and state in 1965,” the Library of Congress documents, “forced the reassessment of this special relationship. In the late 1960s, the Vatican attempted to reform the church in Spain by appointing liberals as interim, or acting, bishops, thereby circumventing Franco’s stranglehold on the country’s clergy. In 1966 the Franco regime passed a law that freed other religions from many of the earlier restrictions, although it also reaffirmed the privileges of the Catholic Church. Any attempt to revise the 1953 Concordat met the dictator’s rigid resistance.”

Clearly, del Toro’s rather mild “swipe” at the Catholic Church isn’t “unfair” in the least.

The cult of unquestioning obedience

But, to my mind, it’s not del Toro’s “swipe” at the Church’s support of Franco’s fascist regime that sticks in conservatives’ collective craw. No, I think it’s del Toro’s denouncement of something much more fundamental to reactionary ideology – the cult of unquestioning obedience.

Pan’s Labyrinth makes it clear that Captain Vidal’s acts of arrogant disdain and savage brutality against those who, for whatever reason, don’t fit into his fascist worldview, stem from his profound lack of the creativity and compassion required so as to formulate and ask questions within (and of) a world dominated by fear and violence.

The humane and compassionate actions of Doctor Ferreiro and the housekeeper Mercedes (Maribel Verdu), on the other hand, both of whom are secretly aiding the rebels, are possible, says the film, as a result of their willingness to envision a world beyond Captain Vidal’s fascist fantasy. Their actions are also only possible as a result of their disobedience of Captain Vidal’s orders.

Likewise, Ofelia’s disobedience of the faun’s demand that she hand over her infant brother, proves to be a deeply significant act of courage and integrity. Such acts are beyond the comprehension of her step-father and the world of fascist mythology he seeks to both build and embody.

As Paul Bond observes, “Vidal, bristling with machismo, fails to notice that . . . Mercedes is spying for the resistance. She was invisible to him because she was a woman, she says when finally discovered. Vidal is similarly uncomprehending when he discovers that Dr. Ferreiro has not simply obeyed his orders.”

Highly authoritarian structures – including religious institutions or, at the very least, the reactionary aspects of any given religious tradition – rely on obedience to maintain their sense of authority and control. In Catholicism, for example, unquestioning obedience to the Church is highly valued. Indeed, advancement up the hierarchical chain of command is contingent on unquestioning obedience. Of course, by “Church,” those who champion such obedience are not referring to the Mystical Body of Christ, which, in the egalitarian spirit of Jesus, means all of us.

Rather, Catholic proponents of unquestioning obedience, when referring to “the Church,” generally mean the Vatican, or more precisely, the institutional component of the Church (comprised chiefly of the curia and magisterium) which rose to prominence in the late nineteenth century at a time when many of its members were fearing and denouncing the democratic spirit sweeping across Europe and threatening their own imperial power and influence. As with a number of issues, the Vatican was on the wrong side of history at that particular time. As a result, it’s now, for all intents and purposes, the last remaining absolute monarchy in Europe and, as such, an often irrelevant and embarrassing bastion of reactionary thought and activism.

Understandably, Catholic proponents of unquestioning obedience view “the Church” as, in the words of Catholic columnist and author Chris McGillion, “a kind of club with an inflexible set of rules, to which all its members must subscribe. Those who don’t . . . are made to feel unwelcome; those who question the rules are asked to leave or forced to go.” Such punishment is warranted as for Catholic members of the cult of unquestioning obedience, public dissent from Church teaching is the greatest of sins. Not surprisingly, such Catholics are highly prone to minimizing and distorting the role of conscience.

Yet important questions need to be asked: Does this “kind of club”-understanding of Church reflect the example of community modeled by Jesus?

Is it the only way to view and understand the reality of Church? Is it even an appropriate way to understand Church?

What are other ways present in our Catholic tradition and experience?

Are some of these more equipped than others to emulate Jesus and thus invite and encourage people to flourish, both individually and communally?

As a gay man within the Catholic Church – a Church I view and experience as being much broader and progressive than simply “the Vatican” – I’ve crossed paths with some Catholics who define themselves in terms of this “club with an inflexible set of rules”-understanding of Catholicism, one focused on the Vatican and unquestioning obedience to it.

Am I saying that obedience has no place in our Catholic faith? Of course not. Nevertheless, I think a way of understanding obedience that is conducive to both individual and communal flourishing is sorely needed. One such understanding has been offered by theologian Diarmuid O’Murchu, who, in his book Poverty, Celibacy, and Obedience: A Radical Option for Life, notes that, “Obedience is not about submitting our will to a higher authority (why then did God give us a will in the first place?) but about exploring and proffering ever new ways to engage responsibly, collaboratively, and creatively with the issues of power and powerlessness that we encounter in daily life. . . . At the end of the day it is not laws but values that touch the depth of our human hearts.”

I’m also not suggesting that there isn’t a place for an institutional component within Catholicism. Yet at the same time, many of us who declare ourselves Catholic don’t recognize the clerical/hierarchical culture of the institutional Church as being an essential component of the Catholic faith.

As I’ve stated in a previous post, I believe we require an institutional church, but it’s not essential that this institution be rigidly hierarchical or dominated by clerics. In fact, many Catholics intuitively sense that such a clerical/hierarchical structure and culture is detrimental to the spirit of the Gospel message. Jesus certainly didn’t model such a structure or culture.

With regards to issues of human sexuality, the clerical/hierarchical culture simply does not reflect for many people – gay or straight – the liberating, life-giving spirit of the Gospel. This doesn’t mean I’m advocating a big sexual free-for-all. I just think that as Catholics, we can do better at recognizing and articulating a sexual theology and ethic that actually reflects people’s experience of God in their relational/sexual lives; a theology that actually cares for and thus listens to people’s real lives in the real world – a world permeated by the sacred.

Spiritual violence

I’ve discovered, however, that there are some gay Catholics (or rather “same-sex attracted” Catholics) who, for whatever reason, can’t or won’t see every aspect of the world – including their God-given sexual orientation and its expression – as infused with God’s loving and transforming presence.

Instead, they rigidly hold to the belief that any sexual orientation other than heterosexual is “ordered to an intrinsic moral evil.” Never mind that countless lesbian and gay Catholic individuals experience God in their loving (and sexually-expressed) relationships with another of the same gender. Such realities are simply not acknowledged, let alone embraced and celebrated.

Now, I’m not for one moment liking Catholics who embrace such a narrow and rigid perspective on homosexuality to the fascists depicted in del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth. However, there are ways other than physical by which one can inflict violence on another; and, without doubt, the language currently employed by the Vatican to describe homosexual orientation and the lives and relationship of gay people who, in good conscience, cannot subscribe to such a simplistic description, is spiritually violent and abusive.

And then of course there’s the Vatican’s complicity in the deaths of gay people throughout history – a complicity that some would like to gloss over, not unlike those who would like to gloss over and forget the fascist atrocities in Franco’s Spain. Yet as Joseph O’Leary, among others, powerfully reminds us: “When the Vatican formulated its official apology for the Inquisition [in 1998], the multitudes burnt as heretics and witches were duly remembered. But no mention was made of the thousands of gay people burnt directly by the Papal States down to 1750 and executed in other states with papal approval.”

“‘Sodomites’ were demonized in exactly the same style as ‘witches’ were,” says O’Leary, “and treated with equal brutality. Sixteenth century missionaries had sodomites burnt in the Philippines at the same time as they were having Jews burnt in India. But there is no evidence that this weighs on the Vatican's conscience.”

Barbara Nicolosi bemoans the fact that half of Pan’s Labyrinth is “dripping with brutal realistic violence . . . blood, blood, blood . . . torture, murder, abuse.” Perhaps she should acquaint herself with the history of our own Catholic Church and its treatment of, among others, gay people. Then again, perhaps the bucketfuls of blood spilt in The Passion of the Christ are the only blood she considers worthy of lamenting.

After all, this is a woman who, while noting that “Christians in entertainment . . . should be talking about everything in a godly way,” nevertheless employs the following language to talk about gay men.

“[We’re] getting drowned in heralds for the sodomites-in-saddles fantasy, Brokeback Mountain.”

“I can’t really recommend [Brokeback Mountain]. It isn’t good enough to justify getting the images in your head of men doing their twisted enemas-as-act-of-love thing.”

I guess gay people can be excluded from being talked about in a “godly way.”

Poetic, ecstatic truth

Increasingly, when reading the attempts of folks like Nicolosi to review films, I’m reminded of what Thom Parham once said in response to the question: “Why Do Heathens Make the Best Christian Films?”

“The answer is pretty much the same problem we find with new novelists who want to write Christian fiction,” Parham says. “The Christian novelist is so focused on their ‘message’ that they become preachers (boring) instead of storytellers (fascinating). There is a severe warning for this type of message-driven writing. The result is more akin to propaganda than art, and propaganda has a nasty habit of hardening hearts.”

Judging from the positive reception that has greeted del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (and Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, for that matter), people aren’t discerning a work of propaganda. Hearts are not being hardened. So why do folks like Nicolosi revile such films?

My sense is that she and others are simply not attuned to fascinating storytelling, let alone to what filmmaker Werner Herzog refers to as “the deeper strata of truth in cinema . . . [the] poetic, ecstatic truth [that is] mysterious and elusive” and which can only be reached “through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

No, the preachers of propaganda (at either end of the political spectrum), like the guardians of orthodoxy, are too stunted in their outlook and outreach to seek and grasp such truth. They’re too preoccupied ensuring unquestioning obedience to a rigidly prescribed way of viewing and reacting to a circumscribed view of the human condition and, in the sphere of religion, a circumscribed view of God’s presence and action in the world.

As such they’re incapable of joining with reviewer Paul Bond in contemplating (much less acknowledging) that Pan’s Labyrinth can be viewed as “a film of great hope and optimism, of defending the imagination under difficult circumstances.”

Creating such a film is “no small thing,” says Bond. “The film ends with a narrative that the princess left only tiny traces of her presence on earth for those able to see them. A single flower blooms on a stunted tree.”

That “stunted tree” is each of us – in one way or another. I appreciate filmmakers like del Toro who can creatively and entertainingly cultivate the blossoming of awareness and compassion in our hearts, who remind us of the possibility, indeed, at times, the absolute necessity of questioning and challenging, resisting and growing.

Although raised a Catholic, del Toro apparently no longer identifies as one – or perhaps more accurately, solely as one. Regardless, his most recent film conveys a deeply spiritual message – one that we all need to hear. For as Joan Cittister, OSB, reminds us: “Spirituality has to do with critiquing . . . . Follow the example of Jesus to question, question, question authority. . . . The courage to question the seemingly unquestionable is the essence of spiritual leadership.”

Recommended Off-Site Link:

Embraced by Many Religions, Labyrinth Allows Broad Discussion of Faith Issues – Matthai Chakko Kuruvila (San Francisco Chronicle, March 7, 2007).

UPDATE: 10 Years Later, Pan’s Labyrinth Still Shines – Travis Newton (Fandom, October 26, 2016).

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• Reflections on the Overlooked Children of Men

• Reflections on Babel and the “Borders Within”

• Revisiting a Groovy Jesus (and a Dysfunctional Theology)

• Christian Draz’s Critique of Brokeback Mountain

• What the Vatican Can Learn from the X-Men

• The New Superman: Not Necessarily Gay, but Definitely Queer

• Alexander’s Great Love

• Reflections on The Da Vinci Code Controversy

• Thoughts on The Da Vinci Code

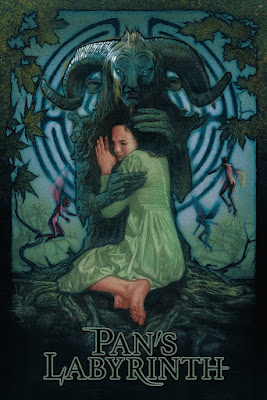

Opening image: Drew Struzan.

9 comments:

Hi Michael

I am simply amazed by the information and the content you have been producing.

Now, I have a question about your blog design. In case you understand the difference between the old blogger and the new, this question may make some sense to you.

How do we insert (using the new blogger format) a horrizontal line between the blog heading and the blogger's profile?

Also, in my case the widget is fixed and doesn't allow to change the image size, etc.

Just as your template, another has achieved this very format. But I dont know how to synchronize both these rows--I mean the blog heading and the blogger's profile.

Any help?

I've read about half of this. What a review! Well done. I'm not sure I agree with all of it. 1000s of priests were killed in socialist spain and I think some of the theocratic tendency was reactionary to that when the natioanlists took power back.

And I am still leaning towards the notion that you might be too tough on the Courage celibates, because i do not think there is a conservative, christian institution for LGBT persons that demands monogamy.

So folks with conservative and obedient persuasions are sort of forced to go all the way to celibacy because there is nothing in between for them...

Hi Winnipeg Catholic,

It's great that you're discovering different parts of my blog. And thanks for your thoughtful comments.

I wonder how healthy it is to rely on any outside entity so as to be monogamous. Shouldn't the love between two people be ultimately what calls them to be monogamous.

After all, straight people have Christian institutions "demanding monogamy" and look at the state of heterosexual marriage!

I think what's needed are structures and communities that encourage and support loving and committed relationships - gay or straight. Monogamy will be a fruit, if you like, of such relationships.

Peace,

Michael

You speak the truth Michael! But I would offer a bit of nuance. The LGBT community is used to only being condemned 100% by institutionalized ethos and obedience. That's different than being lovingly admonished for the promiscuous tendency only, which we hetero males receive (with mixed results).

But I think that an organization that makes ethical demands of its voluntary adherents, that mandates an aesetic code and then teaches & supports that code, well that is important & valuable.

I think that such an organization offers a 'safe harbor' if you will for folks of the strict-mongamy persuasion to meet one another and date and so forth.

I have a healthy hetero marriage but I'm man with male sexual impulses just like you. I think that conservative ethos, institutions, and a wedding band all help me to honor my wedding vows. It also helps that those who do not wish to be 'played' have these mechanisms to sort out the guys cruising for easy sex from those professing a desire for committment.

The other thing I have, when I am feeling a bit too randy, is the example of my forefathers, who lived married, paternal lives that are deeply touching to me. When I think of them behaving otherwise, I would be ashamed, it wouldn't be as holy an example if they were out taking advantage of lonely singles in their spare time. So I try to live their example. What is the example of a gay forefather? What impact on the world should a monogamous gay couple strive to make together?

See the book "Sweet Grapes"...

Finally, such a conservative-gay organization would likely offer a strong advocacy and example.

But what the heck am I doing leaving this comment on the Pan's labyrinth post? Lol, I need to get my butt back to work!

All the Best, -B

Hi Michael,

I enjoyed the review, but now I have actually gotten a chance to view the film.

The special effects, mythos, and fantasy aspect are fun.

The real-world plot, backdrop, and socialist propaganda aspect of it are totally stupid.

We're not using some centuries-old norman conflict as a backdrop, we're using 20th century Spain.

The badguys are all-the-way bad in a way that is stupid and trite. The good guys (the socialists) are all-the-way good in a way that is stupid and trite. "They want everyone to be equal" sneers the bad guy. The bad guys wear their class-A uniforms with perfectly styled wet-look hair cuts the entire movie, so that they can look sinister in an establishment way. The good guys have their flat-hats cocked to the side just so, with a sunset in the background.

For heaven's sake, the movie is just plain stupid.

I have a post on my blog picking on right wing catholics, and I made ample use of Franco-era imagery in my critique of 'cathlofascists'. I am no friend of the fascist regime in spain.

But neither am I a fan of that socialist government, albeit short lived. They murdered thousands of priests. They would have been no better than Stalin and other bannana republic communist sorts of regimes had they succeeded. Franco just had the bad sense to win! Now the left wing in Spain can freely use his fascist legacy to condemn all that is wrong with the world as a right wing issue, when the real issue is autocracy and the repression of liberty.

Now of course I am a libertarian. I don't care whether my opressors where flat-caps or class-A uniforms. Repression is repression, freedom is freedom, this film is silly and just a bit on the trite and stupid side with its over simplification of this very recent conflict.

Hi Winnipeg Catholic,

What can I say? Perhaps only that power has a tendency to corrupt – regardless of whether you’re a conservative, socialist or even a libertarian!

I do think you’re being a bit harsh on the film’s setting – a time, remember, when people from all over the world (including the US) were going to Spain to help defeat a fascist regime. It was a noble cause for many people. Show me any film about a rebel group taking on a brutal and oppressive dictatorship that doesn’t tend to make the “bad guys” really bad, and the rebels extra heroic. Most, if not all, World War II films do this; not to mention fantasy epics such as Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings.

Of course in all such films complex realities are over-simplified: the atrocities of the “bad guys” are heavily focused upon, for example, whereas the atrocities of those resisting and fighting back are quietly down-played or completely ignored.

I’m not sure what you mean by the “short-lived Socialist government” murdering “thousands of priests.” Are you referring to the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939)? If you are, then I think it at least needs to be acknowledged that these murders took place within the context of a Civil War – one that made any effective governing impossible and that saw reigns of both “red” and “white” terror.

I find it interesting how many of those who rightly condemn the murder of members of the Catholic clergy (close to 7,000 according to Wikipedia), fail to similarly condemn the atrocities of the Nationalist forces (numbering in the hundreds of thousands).

Archbishop Oscar Romero of San Salvador once said that if one is to condemn the “responsive violence” of rebel forces, one must also condemn the “oppressive violence” of the regimes to which these rebels are responding.

I'm sure you'd agree.

Peace,

Michael

Hi Michael,

I thought I already responded? Maybe I lost the comment.

I also condemn any and all murderous activities of the Nationalists for what it is worth.

Let's remember that this movie is in Spanish and how a spaniard of any stripe other than socialist/communist would react with regard to a 70 year old event.

You said:

Yet perhaps what is pissing them off most about the film has been left unsaid: its critique of unquestioning obedience.

Well maybe. But maybe it seems like a critique of all things non-socialist too, if you grew up in a society knowing relatives who were killed on either side of the conflict for holding various views or supporting various views. And, if the regime prior to Franco's did not demand lots of obedience I'd be a bit surprised. Marxism tends to be autocratic since that's how 'ol Marx wrote the book.

So when a spaniard (under the current communist government) watches the film and is fluent in the attrocities on both sides, I can't imagine that they would just say "hmmm, this is all about unquestioning obedience, and the Nationalists are just symbolic of that."

What further complicates the whole thing is that Franco never abolished the constitutional monarchy which was eventually restored, making him, strangely, a sort of transitional government for Spain to its current state.

Oh yes, in my lost comment I brought up Star Wars. I think the star wars sort of movie is a bit different.

For example, if the director of PL had made the bad guy secretely a follower of some ancient bad magic and the heroin a follower of ancient good magic and by extension, used the war as a pretext to some other worldly ancient dualistic battle... that would be more like starwards I think.

BTW - I just reread the wikipedia article on Franco. That is one hyper-complex situation. I can see why the artist feels the way he does about the Nationalists, even if it is a little bit one-sided.

36 years of Nationalist rule under Franco starting with autocratic rule during the war and then slowly liberalizing in the 60s to a capitalist state (perhaps not unlike china) and then finally fully liberalizing in the 70s. Then a near-coup in 81 when King Carlos fully reasserts constitutional monarchy.

What a ride!

BTW - the wikipedia article on PL has absotuletly nothing about the controversial aspect at all. It just basically says that everyone loved it.

Post a Comment