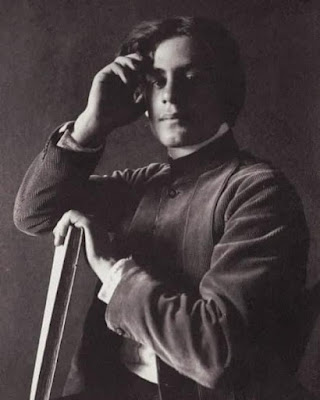

It’s the birthday today of Lebanese-American writer, poet and visual artist Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931).

Born in what is now modern-day Lebanon, Gibran emigrated with his family to the United States at the age of twelve. The family settled in Boston, where they had relatives, and it was there that a charity worker noticed that Gibran appeared to be artistically gifted. He began studying art, in addition to his regular schooling. His mother also wanted him to learn about his Lebanese heritage, and so Gibran went to a prep school and college in Beirut when he was fifteen. He started a literary magazine with a classmate, and was voted “College Poet.” Upon returning to Boston in 1902, at age nineteen, he soon began being invited to social gatherings, where people enjoyed hearing him discuss philosophy and poetry. He continued to show talent as an artist during this time, and first exhibited his drawings in 1904 at the studio of photographer Fred Holland Day, one of his earliest patrons.

On one occasion a man named Alfred A. Knopf was invited to a gathering at Gibran’s apartment. Knopf was starting a publishing company, and when he saw how fascinated people were with Gibran, he decided to offer him a publishing contract. Gibran’s first two books with Knopf weren’t very successful, but his third, a collection of poetic essays called The Prophet (1923), would eventually be translated into more than 50 languages and sell millions of copies worldwide.

Gibran was raised as a Maronite Christian but embraced a variety of beliefs, including Islam and Theosophy. These influences informed the writing of his masterwork, The Prophet, a compilation of 28 inspirational essays composed as prose poems and illustrated with his own drawings. Although it didn’t sell well at first, The Prophet would become the most renowned of the fifteen books of Gibran’s work published in his lifetime and establish him as both a leading figure in Arabic literature as well as one of the bestselling poets of all time. Indeed, Gibran is now the third-best-selling poet in history, after William Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu.

Writes Antonia Pont, Senior Lecturer in Writing and Literature at Deakin University:

[The Prophet], which presents advice on a number of core aspects of being human – such as love, parenting, friendship, Good and Evil, and so on – employs a simple narrative device. An exiled man, Almustafa, who has been living abroad for twelve years, sees the ship that will carry him back “to the isle of his birth” approaching. Filled with grief at his imminent departure, the townspeople gather and beseech him to give them words of wisdom to ease their sorrow. . . . Gibran himself had been in the U.S. for twelve years at the time of writing and, it could be argued, was in a kind of exile from Lebanon, the country of his own birth.

. . . Gibran has been criticised for his style of playing confoundingly but reassuringly on opposites, which, some argue, can mean anything. (One must note, however, that this unsettling of binary structures is a feature of enduring wisdom texts such as the Tao Te Ching, as well as recalling writings of Sufism and other traditions.)

. . . For someone who undoubtedly “made it” (according to the grim criteria of the New World), Gibran may well have had more than a kernel of wisdom and know-how for those trying to survive its heartless, capricious climes. The fact is that millions of people have found momentary respite in his shifting, evocative words.

In a century where authority figures – whether political or representing various spiritual traditions – have seemed not only to fail their flocks, but to have actively betrayed them, Gibran’s perhaps fuzzy but lyrical advice has come to fill a vacuum of integrity and leadership. We need not badger readers of this work (who included, incidentally, the likes of John Lennon and David Bowie) who might use it to express their love, notate their grief, or ease their existential terrors.

The Prophet has worked as a widespread balm, as effectively as anything quick and concise can. Cheaper than an ongoing tithe to pharmaceutical companies, at $8.55, the going rate at Book Depository, it neither incites hatred, nor violence, nor religious divisiveness.

It says the kinds of things that we sometimes wish a trusted other might say to us, to calm us down. In these aggravated times, perhaps we can appreciate its sheer benignity and leave its boggling success be.

In celebrating Kahlil Gibran’s birthday at The Wild Reed, I share one of my favorite poems from The Prophet, “On Self-Knowledge.”

On Self-Knowledge

And a man said, Speak to us of Self-Knowledge.

And he answered, saying:

Your hearts know in silence the secrets of the days and the nights.

But your ears thirst for the sound of your heart’s knowledge.

You would know in words that which you have always known in thought.

You would touch with your fingers the naked body of your dreams.

And it is well you should.

The hidden well-spring of your soul must needs rise and run murmuring to the sea;

And the treasure of your infinite depths would be revealed to your eyes.

But let there be no scales ot weigh your unknown treasure;

And seek not the depths of your knowledge with staff or sounding line.

For self is a sea boundless and measureless.

Say not, “I have found the truth,” but rather, “I have found a truth.”

Say not, "I have found the path of the soul.” Say rather, “I have met the soul walking upon my path.”

For the soul walks upon all paths.

The soul walks not upon a line, neither does it grow like a reed.

The soul unfolds itself, like a lotus of countless petals.

Related Off-site Links:

Kahlil Gibran on Silence, Solitude, and the Courage to Know Yourself – Maria Popova (The Marginalian, November 21, 2019).

Guide to the Classics: The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran – Antonia Pont (The Conversation, November 27, 2018).

Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet: Why Is It So Loved? – Shoku Amirani and Stephanie Hegarty (BBC News, May 12, 2012).

Prophet Motive: The Kahlil Gibran Phenomenon – Joan Acocella (The New Yorker, December 30, 2007).

For more writings of (or about) Kahlil Gibran at The Wild Reed, see:

• Fall Round-Up (2014)

• Out and About – Summer 2015

• Blue Yonder

• Spring . . . Within and Beyond (2022)

• Photo of the Day – March 7, 2020

• Yahia Lababidi: “Poetry Is How We Pray Now”

Opening image: Kahlil Gibran in 1897, photographed by Fred Holland Day.

No comments:

Post a Comment