Part 4: Hanging Rock

This evening I continue my special Wild Reed series documenting my recent visit home to Australia. (To start at the beginning of this series, click here.)

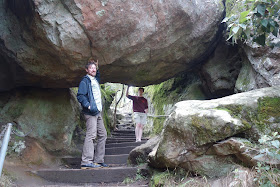

Tonight's installment features photos and commentary from my visit to Hanging Rock with my sister-in-law Cathie and my nephew Mitchell on Friday, May 13.

This was my third visit to Hanging Rock. My first was in 1985 as a 19-year-old college student, while my second was in April of 2003, during a visit home to Australia from the U.S.

On my 2003 visit I was accompanied not only (as in my latest one) by Cathie and Mitchell, but by my parents, Gordon and Margaret Bayly, my brother Chris, and my three other nephews Ryan, Liam, and Brendan.

My interest in and attraction to Hanging Rock began when, as a 10-year-old boy in Australia, I saw Peter Weir's film Picnic at Hanging Rock. This was in 1975, when Weir's adaptation of Joan Lindsay's novel (also titled Picnic at Hanging Rock) was first released. Both Lindsay's book and Weir's film tell the story of a group of students from an exclusive girls' boarding school who mysteriously vanish from a picnic at the Rock on St. Valentine's Day 1900. Weir's film is widely credited as a key work in the "Australian film renaissance" of the mid-1970s. It was also the first Australian film of its era to both gain critical praise and be given a substantial international theatrical release.

Often described as "lush," "atmospheric," and "Gothic," the haunting qualities of Picnic at Hanging Rock certainly left a deep and long-lasting impression on me as a child. Later, as I grew into awareness of my sexuality, the film's themes of oppression and liberation became meaningfully and appealingly apparent to me. I wrote the first version of my essay Rock of Ages: Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock in 1996 for Vertigo, a journal of thought and reflection on sexuality and spirituality published by the theology department of the College of St. Catherine, St. Paul. A second version (which can be found at The Wild Reed here) was written in 2002 as part of my studies in film and theology at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities.

For all these reasons, and for the sheer beauty and uniqueness of the place, Hanging Rock is a very special place for me; a sacred place, really.

Here's a little of what Wikipedia has to say about the "geological marvel" that is Hanging Rock:

The following comprises Chapter 17, the final chapter, of Joan Lindsay's novel Picnic at Hanging Rock. It is accompanied by an image from Peter Weir's film adaptation.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• Rock of Ages: Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock

• Australian Sojourn, May 2016: Part 1 – Maroubra

• Australian Sojourn, May 2016: Part 2 – Morpeth

• Australian Sojourn, May 2016: Part 3 – Melbourne

• Boorganna (Part I)

• Boorganna (Part II)

• On Sacred Ground

• "I Caught a Glimpse of a God"

Images: Michael J. Bayly and Cathie Bayly (except where otherwise noted).

This evening I continue my special Wild Reed series documenting my recent visit home to Australia. (To start at the beginning of this series, click here.)

Tonight's installment features photos and commentary from my visit to Hanging Rock with my sister-in-law Cathie and my nephew Mitchell on Friday, May 13.

This was my third visit to Hanging Rock. My first was in 1985 as a 19-year-old college student, while my second was in April of 2003, during a visit home to Australia from the U.S.

On my 2003 visit I was accompanied not only (as in my latest one) by Cathie and Mitchell, but by my parents, Gordon and Margaret Bayly, my brother Chris, and my three other nephews Ryan, Liam, and Brendan.

My interest in and attraction to Hanging Rock began when, as a 10-year-old boy in Australia, I saw Peter Weir's film Picnic at Hanging Rock. This was in 1975, when Weir's adaptation of Joan Lindsay's novel (also titled Picnic at Hanging Rock) was first released. Both Lindsay's book and Weir's film tell the story of a group of students from an exclusive girls' boarding school who mysteriously vanish from a picnic at the Rock on St. Valentine's Day 1900. Weir's film is widely credited as a key work in the "Australian film renaissance" of the mid-1970s. It was also the first Australian film of its era to both gain critical praise and be given a substantial international theatrical release.

Often described as "lush," "atmospheric," and "Gothic," the haunting qualities of Picnic at Hanging Rock certainly left a deep and long-lasting impression on me as a child. Later, as I grew into awareness of my sexuality, the film's themes of oppression and liberation became meaningfully and appealingly apparent to me. I wrote the first version of my essay Rock of Ages: Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock in 1996 for Vertigo, a journal of thought and reflection on sexuality and spirituality published by the theology department of the College of St. Catherine, St. Paul. A second version (which can be found at The Wild Reed here) was written in 2002 as part of my studies in film and theology at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities.

For all these reasons, and for the sheer beauty and uniqueness of the place, Hanging Rock is a very special place for me; a sacred place, really.

Here's a little of what Wikipedia has to say about the "geological marvel" that is Hanging Rock:

Hanging Rock (formally known as Mount Diogenes) in Victoria, Australia is a distinctive geological formation, 718m above sea level (105m above plain level) on the plain between the two small townships of Newham and Hesket, approximately 70 km north-west of Melbourne and a few kilometres north of Mount Macedon, a former volcano. Hanging Rock, located within the Wurundjeri nation's territory, is best known through the fictional story Picnic at Hanging Rock, written by Joan Lindsay.

Hanging Rock is a mamelon, created 6.25 million years ago by stiff magma pouring from a vent and congealing in place. Often thought to be a volcanic plug, it is not. Two other mamelons exist nearby, created in the same period: Camels Hump, to the south on Mount Macedon and, to the east, Crozier's Rocks. All three mamelons are made of solvsbergite, a form of trachyte only found in two or three other places in the world. As Hanging Rock's magma cooled and contracted it split into rough columns. These weathered over time into the many pinnacles that can be seen today.

. . . Hanging Rock is located within the Wurundjeri nation's territory but they exercised a custodial responsibility on behalf of the surrounding tribes in the Kulin nation. It was a site of male initiation and, as such, entry was forbidden except for those young males being taken there for ceremonial initiation. After colonial settlement the Aboriginal people of the area were quickly dispossessed and forced out of the area by 1844. However, one last initiation ceremony was held there in November 1851 by a Wurundjeri Elder from the Templestowe area in the Yarra Valley. This ceremony was also attended by two young settlers' children, Willie Chivers, 11, and his younger brother Tom, 7, who were being cared for on a daily basis by the tribe after their mother had died. Their father went missing after looking for their mother.

The rock's official name, "Mount Diogenes," was bestowed on it by the surveyor Robert Hoddle in 1844 in keeping with the spirit of several ancient Macedonian names given by Major Thomas Mitchell during his expedition through Victoria in 1836, which passed close to Hanging Rock. Others include Mount Macedon, Mount Alexander and the Campaspe River.

Hanging Rock is the centrepiece for the Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve, a public reserve managed by the Macedon Ranges Shire Council. The reserve includes a horse racing track, picnic grounds, creek, interpretation centre and cafe. The reserve is a habitat for endemic flora and fauna, including koalas, wallabies, possums, phascogales, wedge-tailed eagles and kookaburras.

Above: An image from the website of the Macedon Ranges Shire Council showing an aerial view of both Hanging Rock and the Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve. (Photographer unknown)

On the steep southern facade the play of golden light and deep violet shade revealed the intricate construction of long vertical slabs; some smooth as giant tombstones, others grooved and fluted by prehistoric architecture of wind and water, ice and fire. Huge boulders, originally spewed red hot from the boiling bowels of the earth, now come to rest, cooled and rounded in forest shade.

– Joan Lindsay

Excerpted from Picnic at Hanging Rock

p. 29

Excerpted from Picnic at Hanging Rock

p. 29

As the vertical facade of the Rock drew nearer, the massive slabs and soaring rectangles repudiated the easy charms of its fern-clad lower slopes. Now outcrops of prehistoric rock and giant boulders forced their way to the surface above layers of rotting vegetation and animal decay: bones, feathers, birdlime, the sloughed skins of snakes; some with jagged horns and jutting spikes, obscene knobs and scabby carbuncles; others smoothly humped and rounded by the passing of a million years.

– Joan Lindsay

Excerpted from Picnic at Hanging Rock

p. 78

Excerpted from Picnic at Hanging Rock

p. 78

Upon its release, Picnic at Hanging Rock was praised for its atmospheric cinematography – one which captures beautifully and hauntingly, the unique colors, sounds and contours of the Australian bush.

The opening scene for instance, depicts a forest of eucalyptus trees shrouded in an impenetrable mantle of mist. Silently the mist settles, obscuring the trees but revealing the jagged escarpments and pinnacles of Hanging Rock, aglow in the early morning light.

It is an image that exudes a sense of paradox and mystery, for the towering bulk of volcanic rock appears to hover in space, to hang miraculously within the firmament as if suspended in a timeless realm. The silence accompanying this image is broken only by occasional bird song and by a faint yet ominous sound – the source of which seems to be the very core of the Rock itself.

It is a deeply primordal sound – one that will be echoed on the afternoon of the picnic when Miss McCraw's attention is inexplicibly drawn from her book of trigonometry to the jutting crags of the Rock, and when the schoolgirls Miranda, Marion and Irma explore in awed fascination the time-encoded patterns and formations of the monolith. They are patterns that speak mesmerizingly of transcendence and timelessness, and formations that increasingly seem to invite passage to such realms.

– Michael Bayly

Excerpted from Rock of Ages:

Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock

Excerpted from Rock of Ages:

Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock

Directly ahead, the grey volcanic mass rose up slabbed and pinnacled like a fortress from the empty yellow plain. [They] could see the vertical lines of the rocky walls, now and then gashed with indigo shade, patches of grey green dogwood, outcrops of boulders even at this distance immense and formidable. At the summit, apparently bare of living vegetation, a jagged line of rock cut across the serene blue of the sky.

– Joan Lindsay

Excerpted from Picnic at Hanging Rock

p. 18

Excerpted from Picnic at Hanging Rock

p. 18

It can certainly be an eerie place up near the summit on a somber overcast day when the wind swirls between the gigantic boulders and pinnacles. "We always felt anything could happen on the Rock" were the words of one long-time resident commenting on the picnic mystery.

– Marion Hutton

Excerpted from Hanging Rock:

The Mystical Mount Diogenes

Excerpted from Hanging Rock:

The Mystical Mount Diogenes

The following comprises Chapter 17, the final chapter, of Joan Lindsay's novel Picnic at Hanging Rock. It is accompanied by an image from Peter Weir's film adaptation.

Extract from a Melbourne newspaper, dated February 14th, 1913.

Although Saint Valentine's Day is usually associated with the giving and taking of presents, and affairs of the heart, it is exactly thirteen years since the fatal Saturday when a party of some twenty schoolgirls and two governesses set out from Appleyard College on the Bendigo Road for a picnic to Hanging Rock. One of the governesses and three of the girls disappeared during the afternoon. Only one of them was ever seen again.

The Hanging Rock is a spectacular volcanic uprising on the plains below Mount Macedon, of special interest to geologists on account of its unique rock formations, including monoliths and reputedly bottomless holes and caves, until recently uncharted (1912). It was thought at the time that the missing persons had attempted to climb the dangerous rock escarpments near the summit, where they presumably met their deaths; but whether by accident, suicide or straight out murder has never been established, since the bodies were never recovered.

Intensive search by police and public of the relatively small area provided no clue to the mystery until on the morning of Saturday, February 21st, the Hon. Michael Fitzhubert, a young Englishman holidaying at Mount Macedon (now domiciled on a station property in Northern Queensland), discovered one of the three missing girls, Irma Leopold, lying unconscious at the foot of two enormous boulders. The unfortunate girl subsequently recovered, except for a head injury which left her without memory of anything that had occurred after she and her companions had begun the ascent of the upper levels.

The search was continued for several years under great difficulties, owing to the mysterious death of the Headmistress of Appleyard College within a few months of the tragedy. The College itself was totally destroyed by a bushfire during the following summer. In 1903, two rabbiters camped at the Hanging Rock found a small piece of frilled calico, thought by the police to be part of a petticoat worn on the day of the picnic by the missing governess.

A somewhat shadowy figure appears briefly in this extraordinary story; a girl called Edith Horton, a fourteen-year-old boarder at Appleyard College, who had accompanied the three other girls for a short distance up the Rock. This girl returned at dusk to the other picnickers by the creek below in a state of hysteria, and was unable then, or ever after, to recall anything whatever that had occurred during the interval. Miss Horton recently died in Melbourne without having provided any additional information.

Countess de Latte-Marguery (the former Irma Leopold) is at present residing in Europe. From time to time the Countess has granted interviews to various interested bodies, including the Society for Psychical Research, but has never recalled anything beyond what she was able to remember after first regaining consciousness. Thus the College Mystery, like that of the celebrated case of the Marie Celeste, seems likely to remain forever unsolved.

NEXT: Albury

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• Rock of Ages: Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock

• Australian Sojourn, May 2016: Part 1 – Maroubra

• Australian Sojourn, May 2016: Part 2 – Morpeth

• Australian Sojourn, May 2016: Part 3 – Melbourne

• Boorganna (Part I)

• Boorganna (Part II)

• On Sacred Ground

• "I Caught a Glimpse of a God"

Images: Michael J. Bayly and Cathie Bayly (except where otherwise noted).

No comments:

Post a Comment