News from Minnesota: Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) Catholics and their families and friends are being encouraged to attend the noon Mass at the Cathedral of St. Paul on Pentecost Sunday, June 4.

As Brian McNeill, coordinator of the Minneapolis-based Rainbow Sash Alliance, notes:

Being in Australia until early August, I obviously won’t be able to join my friends – both GLBT and straight – in donning a Rainbow Sash and participating in the Pentecost celebration at the Cathedral of St. Paul.

I did participate in the Mass last year, and was denied communion by the presiding priest (see My Rainbow Sash Experience). Such an experience compelled me to contemplate the following questions:

Despite being refused the bread and wine of the Eucharistic meal, were Rainbow Sash wearers really denied the presence of Christ?

What does our Catholic tradition actually say about the presence of Christ in the Eucharistic experience?

Can one be denied the bread and wine and yet still experience the transforming presence of Christ?

Can anyone really deny us the real presence of Christ?

These questions (and others) are explored by author and scholar Garry Wills in his book Papal Sin: Structures of Deceit (Doubleday, 2000), from which the following is excerpted.

“Receive what you are, the Body of Christ”

Reflections on the Eucharist by Garry Wills

What would a Christian priest have done in the original eucharistic meals? It’s hard to imagine any disciple taking on the role of Jesus as his dramatic representation (eikon). (1) Did the disciples reenact the Last Supper, with one of them playing the role of Jesus? If so, did the priest not eat or drink the bread and wine himself? It is hard to imagine Jesus saying that bread and wine were his body and blood and then eating his own body, drinking his own blood. (2) Where did the playacting aspect of this ceremony end? If the priest played the role of Jesus, did someone else play that of Judas, or of the “beloved disciple” who leaned on Jesus’ breast? If the priest has some magic words to say in the persona of Jesus, why do the words of consecration come down to us in different versions in the New Testament and early Christian writings?

Since it is the Spirit, acting through the whole community, that consecrates, Western theologians are more and more agreeing with Eastern ones that the actual consecrating words are the call (epiklēsis) on the Spirit to “come upon these gifts and make them holy,” not the words quoted from the Last Supper. (3) In fact, the words of Jesus, “Take this and eat, it is my body,” are, on the face of them, words of distribution, which probably followed on his own prayer to the Father, which were the true consecrating words at the Last Supper. As Bernard Häring says: “It is not we priests who consecrate, such that what was bread becomes the presence of Christ. This mystery takes place on the occasion of epiklēsis by the power of the Holy Spirit.” (4) Even if one does not accept this interpretation of the sacrament, it is clear that the Spirit’s presence in the community is what consecrates, so all those stories of priests changing bread and wine with a magic formula are nonsense. They have no such magic, and the Spirit would not act apart from the community.

Since the Spirit consecrates within the community, if one person presides at the Eucharist, it is simply as the community’s representative, not as Christ’s. The first letter of Peter (2:5) refers to Christians as “living stones assembled into a spiritual temple, formed into a holy priesthood to offer spiritual sacrifices.” That is the way, early in the second century, Ignatius of Antioch – usually the first witness called for a belief in Christ’s real presence in the Eucharist – talks of the community. Instead of being fenced off from the altar, the faithful are the altar, just as their flesh is the temple: “You sustain God in you, the altar in you, Christ in you, and holiness in you . . . Guard your flesh as God’s temple.” (5) It is more the faithful who become the body and blood of Christ than bread and wine do.

Within the congregation there is “a union of the flesh and spirit of Jesus Christ.” (6) The faithful are “created again in faith, which is the Lord’s flesh, and love, which is Jesus Christ’s blood.” (7) It makes no sense to form a sacred area away from the faithful, who are the real altars and temples and bearers of Christ’s flesh and blood. They are not distant from the mystery. They are the mystery. For Ignatius, the Eucharist was the full realization of that “one-ing” (henōsis) among themselves he urges on all the communities he addresses.

Almost three centuries later, Augustine was still talking of the faithful as the stuff that is transformed by the Eucharist. He never mentions (any more than the New Testament did, or Ignatius did) the power of the priest to consecrate. He says it is the faithful recipients who make the body of Christ present by becoming it.

Over and over Augustine places the validity of the sacrament in the recipient’s unity with God and each other, not in any preceding words or magic of the priest. He denied that Christ’s risen physical body could be in more than one place. When Christ is said to be in several different places, it is the members of his body in the Christian community that are referred to. (8)

Augustine rejects the idea that teeth and chewing and swallowing make one receive the body of Christ. (9) Augustine says that we cannot take Christ into us. “The symbol is received, it is eaten, it disappears – but can Christ’s body disappear, Christ’s church disappear, Christ’s members disappear? Far from it.” (10) We must be taken into Christ’s body, not he into ours: “We abide in him when we are his members, and he abides in us when we are his temple. And for us to become his members, unity must bind us to each other.” (11) The Eucharistic transformation is, for Augustine, a change of the community into a single thing, and the symbolism that he finds in the Eucharist is not of the physical body of Christ but of the mystical union of his members under the sign of bread, made a unit from many grains of wheat, and wine, made a unit from many grapes.

So clearly is the bread a sign of the unity of Christians that it was customary in Augustine’s time to send some of the bread left over from the eucharistic meal to other communities, expressing a general oneness. (12) That would never happen today, when people think the host could be desecrated if handled by anyone but a priest. Candles were not carried alongside the eulogion (as it was called). The only effect of an unbeliever’s eating the bread is that he or she does not become a member of the body of Christ. There is no actual body in the host to bleed or be abused.

It has scandalized many Catholics that, as the Augustinian scholar F. van der Meer had reluctantly to admit, in all Augustine’s hundreds of sermons delivered at the Eucharistic meal, “he does not speak of a real presence” in the bread and wine. (13)

Augustine in the fourth century, just as Ignatius in the second, would never have thought that reverence to the Eucharist involved removing its mystery from the midst of the believers. They would not have fenced off the altar, since the people were the altar, just as they were the bread lying on it.

[Augustine] wanted no adventitious mystification. He did not wear altar vestments at the Eucharistic meal, but his everyday clothes. He had no taste for pomp. He melted down the precious metals of communion vessels to ransom prisoners. His fellows in Christ were the real vessels of Christ’s body. He agreed with Saint Paul, who said that mystery for its own sake, like speaking in tongues that no one could interpret, was not a service to the community. . . Yet the priest muttering in Latin before modern communities was in effect just speaking to himself and God. The original language of the Mass was whatever tongue the community spoke – Aramaic in Jerusalem, Greek in the diaspora, Latin only after a while in Rome. At the Last Supper Jesus did not speak in some exotic tongue his disciples could not understand.

The need to keep Latin as a mark of caste was demonstrated at the Second Vatican Council, where bishops could not express themselves spontaneously or with subtlety because they were forced to use Latin, yet many begged to keep the dead language that sealed them off from the laity in their church rituals. It was most telling that Cardinal Spellman of New York got up to defend the use of Latin, but spoke it so barbarously that people could not understand him.

Vatican officials feared change in the liturgy for a very real and practical reason. If you take away the magical aura from the Mass, the existence of a priestly caste with ritual purity is hard to justify. If a privileged entrée to sanctuaries from which the laity are excluded is gone, what happens to the rules of Leviticus? That is why Pope Paul VI was forced back on weaker and weaker arguments for preservation of the caste’s celibacy. He tried to say that asceticism is itself a witness to the purity of a person’s dedication. That was true of the desert fathers. But they did not minister to a community – they went off on their spiritual adventure to avoid the duties and entanglements of the priests. Besides, their asceticism was part of an integral life pattern. They fasted, punished their bodies, abstained from company and entertainments and pleasures. The modern priest is not in general terms an ascetic. An ascetic like the Dalai Lama does impress people by the monkish discipline he observes. He is not only celibate. He does not drink alcohol, smoke tobacco, play games, go to the movies.

Priests may today be celibate; but – with some honorable exceptions – they usually maintain a comfortable life style, especially compared with the poor they profess to be serving.

We all know priests with refined tastes in food and drink, nice cars, expensive stereos. If priests are so ready to indulge in other pleasures, then why is celibacy their one abstention? It is not the witness of asceticism in a broader sense that can justify this, but only the sneaking, no longer confessed heritage of the Stoics and Leviticus that makes sex of itself somehow unclean and debasing. The Pope can no longer say that, but his actions reveal his instincts in the matter.

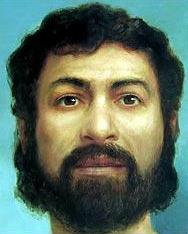

Pope Paul VI says that the priest should resemble Christ. Well, where is Christ to be found on earth these days? A theologian priest I know tells the community when he preaches that he comes to Mass to find Christ, and that he finds him by looking out at the face before him. The Christ to be resembled is there, in the members of his body. That man over there is Christ. So is this woman over here. So, at that moment, are we all. This priest also urges the Augustinian formula when he gives out communion: “Receive what you are, the body of Christ.”

1. Sacerdotalis Caelibatus, paragraph 31.

2. Joachim Jeremias, The Eucharistic Words of Jesus, translated by Norman Perrin (Fortress Press, 1977), p. 212.

3. Yves Congar, I Believe in the Holy Spirit, translated by David Smith (Crossroads, 1997), Vol. III, p. 233.

4. Bernard Haring, Priesthood Imperiled (Triumph Books, 1996), p. 131.

5. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians 9:1; Letter to the Philippians 7:2.

6. Ignatius, Letter to the Magnesians 1:1. Also, Letter to the Trallians, Introduction.

7. Ignatius, Letter to the Trallians 8:1.

8. Augustine, Interpreting John’s Gospel 30.2, 28.2.

9. Ibid., 26.12.

10. Augustine, Sermon 227 (PL 38.1247)

11. Augustine, Interpreting John’s Gospel 27.6.

12. Augustine, Letters 24.6, 31.9, 32.3.

13. F. van der Meer, Augustine the Bishop, translated by Brian Battershaw and G.R. Lamb (Sheed and Ward, 1961), p. 284.

As Brian McNeill, coordinator of the Minneapolis-based Rainbow Sash Alliance, notes:

This will be the sixth year that Twin Cities GLBT Catholics have joined their sisters and brothers for Eucharist on Pentecost at the Cathedral wearing the Rainbow Sash. Although criticized by some, most notably Archbishop Flynn, as a symbol of protest, the Rainbow Sash is actually a symbol of celebration. On the day when the Church celebrates the coming of the Holy Spirit, and the gifts of the Spirit, GLBT Catholics put on the Rainbow Sash to praise and thank God for the gift of their GLBT sexuality. Many remember when Dr. David Pence and his group, Ushers of the Eucharist, blocked the aisles of the Cathedral to prevent Rainbow Sash wearers from receiving communion. After consulting with the liturgical authorities at the Vatican, Archbishop Flynn has opted to agree with Dr. Pence’s criticism. On Pentecost 2005, all those wearing the Rainbow Sash at the Cathedral were denied communion. We hope and pray that the archbishop will have a change of heart in 2006.

Being in Australia until early August, I obviously won’t be able to join my friends – both GLBT and straight – in donning a Rainbow Sash and participating in the Pentecost celebration at the Cathedral of St. Paul.

I did participate in the Mass last year, and was denied communion by the presiding priest (see My Rainbow Sash Experience). Such an experience compelled me to contemplate the following questions:

Despite being refused the bread and wine of the Eucharistic meal, were Rainbow Sash wearers really denied the presence of Christ?

What does our Catholic tradition actually say about the presence of Christ in the Eucharistic experience?

Can one be denied the bread and wine and yet still experience the transforming presence of Christ?

Can anyone really deny us the real presence of Christ?

These questions (and others) are explored by author and scholar Garry Wills in his book Papal Sin: Structures of Deceit (Doubleday, 2000), from which the following is excerpted.

____________________________________

“Receive what you are, the Body of Christ”

Reflections on the Eucharist by Garry Wills

What would a Christian priest have done in the original eucharistic meals? It’s hard to imagine any disciple taking on the role of Jesus as his dramatic representation (eikon). (1) Did the disciples reenact the Last Supper, with one of them playing the role of Jesus? If so, did the priest not eat or drink the bread and wine himself? It is hard to imagine Jesus saying that bread and wine were his body and blood and then eating his own body, drinking his own blood. (2) Where did the playacting aspect of this ceremony end? If the priest played the role of Jesus, did someone else play that of Judas, or of the “beloved disciple” who leaned on Jesus’ breast? If the priest has some magic words to say in the persona of Jesus, why do the words of consecration come down to us in different versions in the New Testament and early Christian writings?

Since it is the Spirit, acting through the whole community, that consecrates, Western theologians are more and more agreeing with Eastern ones that the actual consecrating words are the call (epiklēsis) on the Spirit to “come upon these gifts and make them holy,” not the words quoted from the Last Supper. (3) In fact, the words of Jesus, “Take this and eat, it is my body,” are, on the face of them, words of distribution, which probably followed on his own prayer to the Father, which were the true consecrating words at the Last Supper. As Bernard Häring says: “It is not we priests who consecrate, such that what was bread becomes the presence of Christ. This mystery takes place on the occasion of epiklēsis by the power of the Holy Spirit.” (4) Even if one does not accept this interpretation of the sacrament, it is clear that the Spirit’s presence in the community is what consecrates, so all those stories of priests changing bread and wine with a magic formula are nonsense. They have no such magic, and the Spirit would not act apart from the community.

Since the Spirit consecrates within the community, if one person presides at the Eucharist, it is simply as the community’s representative, not as Christ’s. The first letter of Peter (2:5) refers to Christians as “living stones assembled into a spiritual temple, formed into a holy priesthood to offer spiritual sacrifices.” That is the way, early in the second century, Ignatius of Antioch – usually the first witness called for a belief in Christ’s real presence in the Eucharist – talks of the community. Instead of being fenced off from the altar, the faithful are the altar, just as their flesh is the temple: “You sustain God in you, the altar in you, Christ in you, and holiness in you . . . Guard your flesh as God’s temple.” (5) It is more the faithful who become the body and blood of Christ than bread and wine do.

Within the congregation there is “a union of the flesh and spirit of Jesus Christ.” (6) The faithful are “created again in faith, which is the Lord’s flesh, and love, which is Jesus Christ’s blood.” (7) It makes no sense to form a sacred area away from the faithful, who are the real altars and temples and bearers of Christ’s flesh and blood. They are not distant from the mystery. They are the mystery. For Ignatius, the Eucharist was the full realization of that “one-ing” (henōsis) among themselves he urges on all the communities he addresses.

Almost three centuries later, Augustine was still talking of the faithful as the stuff that is transformed by the Eucharist. He never mentions (any more than the New Testament did, or Ignatius did) the power of the priest to consecrate. He says it is the faithful recipients who make the body of Christ present by becoming it.

Over and over Augustine places the validity of the sacrament in the recipient’s unity with God and each other, not in any preceding words or magic of the priest. He denied that Christ’s risen physical body could be in more than one place. When Christ is said to be in several different places, it is the members of his body in the Christian community that are referred to. (8)

Augustine rejects the idea that teeth and chewing and swallowing make one receive the body of Christ. (9) Augustine says that we cannot take Christ into us. “The symbol is received, it is eaten, it disappears – but can Christ’s body disappear, Christ’s church disappear, Christ’s members disappear? Far from it.” (10) We must be taken into Christ’s body, not he into ours: “We abide in him when we are his members, and he abides in us when we are his temple. And for us to become his members, unity must bind us to each other.” (11) The Eucharistic transformation is, for Augustine, a change of the community into a single thing, and the symbolism that he finds in the Eucharist is not of the physical body of Christ but of the mystical union of his members under the sign of bread, made a unit from many grains of wheat, and wine, made a unit from many grapes.

So clearly is the bread a sign of the unity of Christians that it was customary in Augustine’s time to send some of the bread left over from the eucharistic meal to other communities, expressing a general oneness. (12) That would never happen today, when people think the host could be desecrated if handled by anyone but a priest. Candles were not carried alongside the eulogion (as it was called). The only effect of an unbeliever’s eating the bread is that he or she does not become a member of the body of Christ. There is no actual body in the host to bleed or be abused.

It has scandalized many Catholics that, as the Augustinian scholar F. van der Meer had reluctantly to admit, in all Augustine’s hundreds of sermons delivered at the Eucharistic meal, “he does not speak of a real presence” in the bread and wine. (13)

Augustine in the fourth century, just as Ignatius in the second, would never have thought that reverence to the Eucharist involved removing its mystery from the midst of the believers. They would not have fenced off the altar, since the people were the altar, just as they were the bread lying on it.

[Augustine] wanted no adventitious mystification. He did not wear altar vestments at the Eucharistic meal, but his everyday clothes. He had no taste for pomp. He melted down the precious metals of communion vessels to ransom prisoners. His fellows in Christ were the real vessels of Christ’s body. He agreed with Saint Paul, who said that mystery for its own sake, like speaking in tongues that no one could interpret, was not a service to the community. . . Yet the priest muttering in Latin before modern communities was in effect just speaking to himself and God. The original language of the Mass was whatever tongue the community spoke – Aramaic in Jerusalem, Greek in the diaspora, Latin only after a while in Rome. At the Last Supper Jesus did not speak in some exotic tongue his disciples could not understand.

The need to keep Latin as a mark of caste was demonstrated at the Second Vatican Council, where bishops could not express themselves spontaneously or with subtlety because they were forced to use Latin, yet many begged to keep the dead language that sealed them off from the laity in their church rituals. It was most telling that Cardinal Spellman of New York got up to defend the use of Latin, but spoke it so barbarously that people could not understand him.

Vatican officials feared change in the liturgy for a very real and practical reason. If you take away the magical aura from the Mass, the existence of a priestly caste with ritual purity is hard to justify. If a privileged entrée to sanctuaries from which the laity are excluded is gone, what happens to the rules of Leviticus? That is why Pope Paul VI was forced back on weaker and weaker arguments for preservation of the caste’s celibacy. He tried to say that asceticism is itself a witness to the purity of a person’s dedication. That was true of the desert fathers. But they did not minister to a community – they went off on their spiritual adventure to avoid the duties and entanglements of the priests. Besides, their asceticism was part of an integral life pattern. They fasted, punished their bodies, abstained from company and entertainments and pleasures. The modern priest is not in general terms an ascetic. An ascetic like the Dalai Lama does impress people by the monkish discipline he observes. He is not only celibate. He does not drink alcohol, smoke tobacco, play games, go to the movies.

Priests may today be celibate; but – with some honorable exceptions – they usually maintain a comfortable life style, especially compared with the poor they profess to be serving.

We all know priests with refined tastes in food and drink, nice cars, expensive stereos. If priests are so ready to indulge in other pleasures, then why is celibacy their one abstention? It is not the witness of asceticism in a broader sense that can justify this, but only the sneaking, no longer confessed heritage of the Stoics and Leviticus that makes sex of itself somehow unclean and debasing. The Pope can no longer say that, but his actions reveal his instincts in the matter.

Pope Paul VI says that the priest should resemble Christ. Well, where is Christ to be found on earth these days? A theologian priest I know tells the community when he preaches that he comes to Mass to find Christ, and that he finds him by looking out at the face before him. The Christ to be resembled is there, in the members of his body. That man over there is Christ. So is this woman over here. So, at that moment, are we all. This priest also urges the Augustinian formula when he gives out communion: “Receive what you are, the body of Christ.”

1. Sacerdotalis Caelibatus, paragraph 31.

2. Joachim Jeremias, The Eucharistic Words of Jesus, translated by Norman Perrin (Fortress Press, 1977), p. 212.

3. Yves Congar, I Believe in the Holy Spirit, translated by David Smith (Crossroads, 1997), Vol. III, p. 233.

4. Bernard Haring, Priesthood Imperiled (Triumph Books, 1996), p. 131.

5. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians 9:1; Letter to the Philippians 7:2.

6. Ignatius, Letter to the Magnesians 1:1. Also, Letter to the Trallians, Introduction.

7. Ignatius, Letter to the Trallians 8:1.

8. Augustine, Interpreting John’s Gospel 30.2, 28.2.

9. Ibid., 26.12.

10. Augustine, Sermon 227 (PL 38.1247)

11. Augustine, Interpreting John’s Gospel 27.6.

12. Augustine, Letters 24.6, 31.9, 32.3.

13. F. van der Meer, Augustine the Bishop, translated by Brian Battershaw and G.R. Lamb (Sheed and Ward, 1961), p. 284.