A review of Naomi Greene's

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Cinema as Heresy

In her 1990 book Pier Paolo Pasolini: Cinema as Heresy, Naomi Greene, professor of French and Film Studies at the University of California, aims to trace both the evolution of Pasolini's ideas and the details of his troubled personal life. She achieves this through a careful and thorough analysis of each of Pasolini's twenty-three films – an analysis that pays particular attention to what Margaret Miles terms the underlying social "matrix" of film. Accordingly, the book primarily spans the time frame from 1950, the year Pasolini settled in Rome, to 1975, the year of his brutal murder – seemingly at the hands of a young male prostitute.

It is universally acknowledged that Pier Paolo Pasolini was one of the most controversial European intellectuals of the postwar era. An Italian-born poet, novelist, essayist, filmmaker, and political commentator, Pasolini is often (though narrowly) remembered for his vivid use of juxtaposed imagery to expose the hollowness of modern capitalistic society. His last film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, most resolutely and shockingly exemplifies this.

Set in Italy during the last days of World War II, Salò (right) graphically links fascism and sadism. The film was initially banned virtually everywhere, and to this day continues to generate controversy. Nevertheless, Greene is adamant that all of Pasolini's films raise important cultural and political issues, and that each relates not only to aspects of his personal life but to broader historical developments – chief among them the rise of the economic doctrine of neoliberalism.

Greene's critical awareness of film's underlying social, political, and cultural matrix not only aligns her hermeneutics with Margaret Miles' book Seeing and Believing: Religion and Values in the Movies, but also with David Jasper's critique of the profit-driven Hollywood film industry and its aversion to works that challenge the viewer and/or question the social status quo. Both Miles' and Jasper's understanding of film presupposes that film can implicitly, if not explicitly, address the profoundly religious question of how human beings should live. Intrinsic to this is the belief that film can raise and/or respond to questions about the nature and destiny of human existence, and the journey – personal and communal – to human and thus spiritual authenticity.

Miles, for instance, sees film as a "contemporary cultural text," as the forum in which "values come out into the open, clash, and are violently or peacefully negotiated." At the heart of both Pasolini's life and art this clash of values can be discerned. His response to the 1968 student uprisings in Paris clearly articulates his understanding of the nature and crisis of this clash. For Pasolini, the student protests "signaled not the birth of a new revolution but, instead, the death throes of the struggle for social justice which had appeared so compelling to him and others of his generation after [World War II]" (p. 174). Just one year before his death, writes Greene, Pasolini "described the students' revolt as a 'scream of pain,' a last desperate and important cry that came from the unacknowledged, and probably unconscious, realization that an era was over: 'technological capitalism' had triumphed and its victory precluded 'any possible relation with Marxism.'" (pp 174-175). It is against this social backdrop and the personal struggles of Pasolini, as both an openly gay man and a Marxist within a world he perceived sinking into the new fascism of capitalist neoliberalism, that Greene examines his creative work as a filmmaker.

In the first chapter of Cinema as Heresy, Greene perceptively identifies a number of key events in Pasolini's early life that account for his future political, artistic and personal development. Yet she also notes that a "sex scandal" in his hometown resulted in the young Pasolini being expelled from the Communist party and banned from teaching in the state schools. Accordingly, Pasolini was forced to relocate to Rome in 1950, where, after a brief and unsatisfying stint as a screenwriter, he decided to work as a film director. Cinema, Greene notes, always made Pasolini feel "closer to reality":

Like dialect, which offered what he called a "carnal approach" to the world of peasants, [Pasolini] believed that cinematic expression, that is, the object-like concreteness of cinema," permitted him to "reach life more completely. To appropriate it, to live it through recreating it. Cinema permits me to maintain contact with reality-a physical, carnal contact, and even one, I'd say, of a sensual kind." (p. 19)

Greene suggests that Pasolini's comparison between cinema and life sprang from "a deep wish to embrace and encompass reality; he wanted not only to penetrate to the heart of the real but to decipher it, interpret it, wrest its secrets from it as from a text" (p. 101). Beyond the anti-naturalism in Pasolini's films, says Greene, "lay, undoubtedly, a desire to exchange the social and historical world of the neorealists for a universe that opens upon the sacred, the mythic, the epic" (p. 43). Furthermore, Pasolini's films reflect his belief that "only 'prehistoric' cultures [as depicted in Medea] and the sub proletariat [as in Accattone] could achieve the mythic or epic sense which, he felt, had vanished from the contemporary world" (p. 43). Refusing to separate cinema and life, "Pasolini desired, above all, to overcome the impossible gap between the real and the 'represented'" (p. 101). Such a desire, notes Greene is not without precedence:

Pasolini's impossible desire – to seize the world directly without the mediating screen always implicit in artistic creation – is clearly part of a long poetic tradition that may have reached its apogee in the symbolist poets he so loved. In one famous poem, Rimbaud speaks of "seizing" the dawn, while the extraordinarily hermetic Mallarme, who dreamed of turning the world into a "book," wanted the very sounds of words to evoke, to correspond with, meaning. The symbolist quest could almost be seen as a hermetic echo of primitive man's refusal to separate words and things, a refusal that evoked lyrical praise from Pasolini, who described it thus: "Magical formula, prayer, and miraculous identification with the thing pointed to." (p. 102).

Pasolini was a great admirer of the ethnologist Mircea Eliade, whose insights Michael Bird in Religion in Film drew on to talk about film's ability to potentially serve as hierophany – as a manifestation of the sacred. Using Eliade as his reference point, Bird (and, I suggest, the films of Pasolini) understand hierophany as "the manifestation of something of a wholly different order, a reality that does not belong to our world, in objects that are an integral part of our natural 'profane' world." Note for instance the words Pasolini places on the lips of the centaur in his 1969 film Medea: "All is sacred! There is nothing natural in Nature . . . Wherever your eye roams a god is hidden. And if he be not there, the signs of his presence are there-in silence, or the smell of the grass, or the freshness of water. Yes, everything is holy!" Yet the sacred was for Pasolini, a potentially dangerous and fickle reality, for the centaur also warns the young Jason that "holiness is also a malediction. The god that loves, at the same time hates."

Thus, though he often labeled himself an atheist, Pasolini nevertheless sought to express though his films, his conviction that the sacred quality of life, the inseparableness of "words and things" which he understood as both blessing and curse, is to be found not in any religion, but in life itself-in the naturalness of the created, sensual world. Since no religion could adequately express the depth of Pasolini's feeling for the sacred naturalness of life, he opted to renounce them all. Yet as Greene points out, "he never denied that Christianity was deeply rooted within him" (p. 27) and many have observed that his perception of the natural sacredness of life enabled Pasolini to make perhaps one of the most profoundly "religious" films ever – The Gospel According to Matthew – in 1964.

Greene notes that many have criticized the fact that the world presented in Pasolini's films is one where everything is predestined, highly patterned, and controlled. Tragic foreshadowings abound and there is a distinct and ominous fatalism that imbues all his films – even those like 1974's Il fiore delle mille e una notte (The Flower of the One Thousand and One Nights), the final part of his Trilogy of Life series. In one of the many interconnected tales of this sensuality-affirming film, a shipwrecked prince (above) comes upon a young lad who has been hidden in a beautifully furnished underground chamber in order to forestall a prophecy announcing his imminent murder:

The prince laughs at the boy's fears; they bathe, caress each other, and fall asleep in the same bed. But destiny is not to be thwarted: the prince awakens in a trance, slips off the sleeping lad's clothes, and stabs him to death before climbing back into bed.

. . . Since the "sign" made by destiny involves the birth of desire, the film itself becomes a chain of desires, an erotic current that seizes its mesmerized victims and carries them along, sometimes to happiness but more often to death. These passive beings may suffer from what Pasolini called "epistemological anxiety" concerning their fate, but they know that all resistance is vain: "What God wants will happen," murmurs one, "what God does not want will not happen". (pp. 195-196)

Greene notes that Pasolini's "taste for such absolutes was, he once confessed, only 'completely satisfied by the act of death, which seems to me the most mythic and epic aspect there is'" (p. 43). Misery too, Pasolini believed, is – because of its deepest nature – epic: "In a certain sense." he once remarked, "the elements at work in the psychology of someone who is wretched, poor, and sub-proletarian are always pure" (p. 44).

As mentioned previously, Pasolini lamented the fact that the sense of the epic, the sacred, mediated through "luminous" nature and a deep sense of human experience, had vanished with the rise of capitalistic culture. Nowhere is this explored and expressed more powerfully then in his 1969 film Medea – wherein the inhabitants of ancient Colchis, including the High Priestess Medea (played by Maria Callas), are depicted as perceiving and responding to the presence of the sacred in their land. The marauding Jason and his companions, however, show no respect for either the land or others' connection to it. Jason represents Pasolini's view of the secularized First World – one dominated by logic and wherein acknowledgement of the sacred, of mystery, has no part.

The corruption of Medea, manifested in her willingness to assist Jason in his theft of the sacred relic of the golden fleece, symbolizes for Pasolini the all too common fate of indigenous cultures exposed to the conquering, consumerist mentality of the secularized nations of the West. As enticing as the First World nations may appear, Pasolini's Medea shows that a fatal price is paid for aligning with them. The fate of Medea symbolizes and personalizes this price – "The poor soul has had a reverse conversion," notes Jason's mentor the centaur, "and [she] has never recovered from it." The people of Colchis have an ominous premonition of this "reverse conversion," and they accurately connect their sense of dread with the arrival of Jason:

The sky was the boundary of our kingdom

But Jason will come and he will pierce the sky

And bring an end to our kingdom

He will laugh while we cry

For the name of blasphemy is on his lips

And where he passes, all will turn barren

He will bring an end to our kingdom

And the blood shed because of him

Will erase forever the sacred blood of God.

We know the vineyard but not the sea

We know fields of peas and garlic but not the sea

And Jason comes from the sea

He comes from the sea.

We will fall like dead upon the ground

And when we open our eyes again

We will see things forever abandoned by God.

By betraying and abandoning her land and her people, Medea is shown to loose touch with her religious beliefs and thus her connection to the land ("Speak to me Earth! I no longer hear you! Earth, where is your meaning? I touch the earth with my feet but do not recognize it!"). Living in exile as an "archaic woman" in Greece – in "a world that doesn't believe in anything in which she always believed" – Medea is feared as a foreigner and treated as an outcast. In time – driven to desperation and rage – she commits a horrific act of vengeance.

Greene perceptively reads the character of Medea as a symbol of early religious sensibilities abruptly exposed to, and immersed in, a predominately secular and profane world. Jason represents this "new" world – enticing yet devoid of depth, of the mythic, the epic, the sacred. The film's ultimate and tragic outcome is a clear indictment of not only the industrialized/secularized First World's violent exploitation and oppression of so-called Third World countries, but the responsive violence that can result.

Oppressive (and sadistic) violence is the hallmark of Pasolini's last film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom – a film made purposely, observes Greene, to "resist consumption" (p. 217). She notes that when discussing Salò's scenes of coprophagy, Pasolini deemed them "a metaphor for the fact that 'producers, the manufacturers force the consumer to eat excrement'" (p. 217). Such scenes, as deplorable as many see them, nevertheless reflected the "positive value" that Pasolini's saw in innovative or extremist art: "By challenging the code, he argued, such art questions and subverts the culture and society embedded in it" (p. 222). Accordingly, every film of Pasolini's, Green observes, was part of "a pattern of transgression and persecution" (p. 220). He saw himself as a "martyr-director," continually and defiantly, "on the frontlines of linguistic and social/political transgression" (p. 221):

[Pasolini's] cinema was the most was the most public and spectacular manifestation of a perpetual struggle for "permanent invention," a struggle constantly renewed as each new film opposed still another constellation of formal and social conventions. By a transgression that inevitably and demonstrably revealed the "infinite possibilities of modifying and enlarging the code," Pasolini challenged the cultural limits, the social vision, reflected and perpetuated in the code. His insistence on the moral implications of culture was, perhaps, frequently disturbing and often unfashionable, but it was largely this very insistence that made him one of the central figures of our time. (p. 222)

To challenge the rise of the dehumanizing and consumerist economic/social system of neoliberalism, Pasolini created Salò – a film so dehumanizing that its message lies "in its desire to be unbearable . . . its refusal to be consumed" (p. 217). Greene also records critic Renato Tomasino's observation that Salò is not a value, neither of use nor exchange . . . it never sought a public . . . Hence Salò is not a product . . . it is the ultimate defeat of capitalisim" (p. 217).

To be sure, Pasolini's films reflect an acute awareness of their underlying social/economic matrix, and reading Greene's compelling book on Pasolini's life and art, I frequently found myself in agreement with Pasolini's analysis of neoliberalism. Yet I find many of the ways in which he chose to respond to this analysis problematic. Certainly, Pasolini's art advocates resistance to neoliberalism, but ultimately, given his mounting pessimism and hopelessness (he renounced, for instance, his Trilogy of Life series of films before embarking on Salò), Pasolini offers no appealing and/or affirming way that we, as humans, should live and respond in the face of dehumanizing oppression, and the question has to be asked, why is this so?

For a start, Pasolini's sense of being a "martyr-director" excludes a sense of communal solidarity and activism. Also, his world of absolutes prevents connection-making or bridge-building between the First World and the Third World. Thus the growing global resistance to neoliberalism – most resolutely manifested for First Worlders in Seattle in 1999, but present for decades in the global south, goes untapped.

Second, Pasolini's concept of the sacred is limited by a narrow perception of God as "puppet-master," as an outside entity that humanity either slavishly reacts to or pays the price for its transgression. Though Pasolini acknowledged the presence of the sacred in "objects" outside the human person, he does not appear to have recognized the sacred in processes within the human and in experiences shared among humans. Accordingly, there is no sense of the sacred as an inner reality that we are invited to embrace and journey with – personally and communally.

Finally, Pasolini's "taste for absolutes," Greene observes, was, he once confessed, only "completely satisfied by the act of death," which seemed to him the most mythic and epic aspect there is. I would counter such a statement with the suggestion that it is transformation (often expressed religiously as resurrection) that is the most mythic and epic aspect – and one that leaves a lot more room for creative response to adversity than, as Salò suggests, the eating of shit.

Greene concludes Cinema As Heresy by declaring Pasolini "one of the most radical and prophetic voices of our century" (p. 223). Thankfully, she does not make such a statement before eloquently acknowledging the ambiguous complexity of her subject:

If [Pasolini's many critics] are not wrong, neither are they totally right. Fueled by his neuroses, Pasolini scandalous art also transcends them. If his sexuality drew him to underdeveloped countries, his love for the Third World led to striking films dealing with the clash of civilizations, the very nature of the West. If an exacerbated sensibility, a sense of otherness. led him to denounce modern society as the "new" fascism, his fear of the media and cultural leveling has not, alas, been proven wrong. (p. 223)

Through their genesis in response to injustice and their creative and boundary-pushing process of creation, the works of Pasolini do offer an example of challenging and resisting adversity and oppression. Yet the ultimate message of these films is informed, I feel, by a flawed and limited understanding of the sacred, and an absence of any spirit of communal solidarity. Thus, perhaps like all human-crafted hierophanies, they not only reveal but also conceal. Through its critical examination of the life and art of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Naomi Greene's Cinema as Heresy powerfully illuminates such paradox – a paradox that for some, remains the greatest heresy of all.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• Pasolini's "Wrathful Christ"

• Callas Went Away

• Remembering Callas

• "This Light Breeze that Loves Me": Theological Reflections on Hamam: The Turkish Bath

• Rock of Ages: Theological Reflections on Picnic at Hanging Rock

• Pan’s Labyrinth: Critiquing the Cult of Unquestioning Obedience

• Reflections on the Overlooked Children of Men

• Reflections on Babel and the “Borders Within”

• What the Vatican Can Learn from the X-Men

• Remembering a Daring Cinematic Exploration

• John Schlesinger's Sunday Bloody Sunday: "A Genuinely Radical Film"

• Chris Mason Johnson's Test: A Film that "Illuminates Why Queer Cinema Still Matters"

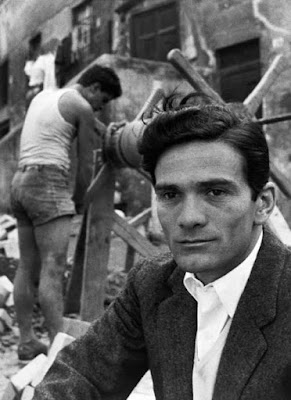

Opening image: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Trastevere, Rome, 1953. (Photographer unknown).

No comments:

Post a Comment