I’ve also finally viewed my first Dirk Bogarde film – though it wasn’t one I found in a video store but rather one that was recently broadcast in the early hours of the morning by the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC).

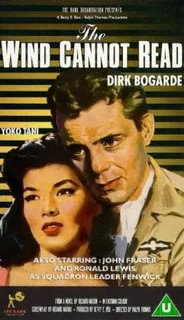

The film shown was 1958’s The Wind Cannot Read, which, says Coldstream, was “Richard Mason’s adaptation of his own novel about a doomed wartime love affair between a grounded RAF officer and a Japanese language teacher”.

The film shown was 1958’s The Wind Cannot Read, which, says Coldstream, was “Richard Mason’s adaptation of his own novel about a doomed wartime love affair between a grounded RAF officer and a Japanese language teacher”.The film, nicknamed “the illiterate fart” by cast and crew, was partly shot in India, where much of the story was set. “The Red Fort was visited,” documents Coldstream, “the Taj Mahal was swooned over, polo was watched, Indira Gandhi was met and a perfectly serviceable film made, its faintly risible action outweighed by [Bogarde’s Flight-Lieutenant character’s] tender romance with [the Japanese language teacher] – played by Toko Tani.”

The most interesting aspect of The Wind Cannot Read is the fact that, as Coldstream notes, the film “yields the prize” for “collectors of those few moments” when Dirk and his real life partner Tony Forwood (pictured at left) share a screen.

The most interesting aspect of The Wind Cannot Read is the fact that, as Coldstream notes, the film “yields the prize” for “collectors of those few moments” when Dirk and his real life partner Tony Forwood (pictured at left) share a screen.This “prize” is “an exchange of dialogue, with [Tony] as a senior officer, interrogation on his mind, telling Dirk as they enter a compound full of Japanese prisoners: ‘Shan’t keep you a minute. I’d like to take another crack at Corporeal Tanaka.’”

Yet the one Dirk Bogarde movie that I really want to see is the landmark 1961 film Victim.

According to Stephen Bourne in his study of homosexuality in the British cinema, Victim “had an enormous impact on the lives of gay men who, for the first time, saw credible representations of themselves and their situations in a commercial British film.”

According to John Coldstream, scene 112 of Victim “was, and remains, the most important of [Bogarde's] acting life. Much of it he himself wrote, or rewrote”. Coldstream then goes on to set the scene: “Confronted by his beautiful wife, Laura, [Dirk’s character, barrister Melville Farr] is asked to explain who this Boy Barrett was, how they knew each other, and why Mel stopped seeing him”.

In the film Mel eventually responds:

Alright – alright, you want to know. I’ll tell you – you won’t be content until I tell you, will you – until you’ve RIPPED it out of me. I stopped seeing him because I WANTED him. Can you understand – because I WANTED him. Now what good has that done you?

Notes Coldstream: “Originally the speech read: ‘You won’t be content till I tell you. I put the boy outside the car because I wanted him. Now what good has that done you?’ The force with which Dirk delivered his extra dialogue to [co-star] Sylvia Syms made it unforgettable. It was the moment when the matinée idol donned a new cloak of seriousness; when ‘Peter Pan’ grew up; when ‘Dorian Gray’ allowed us with him to take a peep into the attic.”

Writer Andy Medhurst notes that “Victim’s intentions were to support the recommendations of the Wolfenden Report, which advocated the partial decriminalisation of male homosexual acts, but the emotional excess of Bogarde’s performance [. . .] pushes the text beyond its liberal boundaries until it becomes a passionate validation of the homosexual option. Simply watch the ‘confession’ scene for proof of this.”

Sylvia Syms agrees that the film itself was a brave undertaking – even “revolutionary” – but, says Coldstream, “she does not sign up completely to the general view that it was an act of courage for Dirk to play Mel: ‘They say he was so brave to play this man with those feelings. But look at the lines he himself wrote. He was frightened of those emotions, and didn’t want to admit them, but, when he had to, he wanted to play them with great truth’”.

In his biography of Bogarde, John Coldstream writes that “[t]he ultimate accolade for what Dirk called this ‘modest, tight, neat little thriller’ would come to him in the summer of 1968, a year after the Sexual Offences Act passed through Parliament and into law. On 5 June Lord (‘Boofy’) Arran, who in 1965 had introduced the legislation in the House of Lords, wrote to Dirk that he had just seen Victim for the first time – on television – ‘and I just want to say how much I admire your courage in undertaking this difficult and potentially damaging part’. He said he understood that it was in large part responsible for a swing in popular opinion, as shown by the polls, from forty-eight per cent to sixty-three per cent in favour of reform. Lord Arran concluded: ‘It is comforting to think that perhaps a million men are no longer living in fear.’”

What a pity that this liberation from fear never fully extended to Dirk himself. Indeed, having completed Coldstream’s biography on Dirk, I’m left with a portrait of a gifted actor and author who, although capable of great graciousness and charm, was nevertheless, at a very deep level, an unhappy and embittered man.

“He had a lot of guilt in him and he carried it around like a sort of knapsack”, says writer Sheridan Morley. “And yet, when you pinned it down, there was nothing really for him to feel guilty about at all.”

Bogarde obviously saw things differently. Indeed, throughout his life he viewed and discussed matters relating to homosexuality, including his own, with at times a certain distaste (not unlike, incidentally, his biographer John Coldstream) and at other times, flat denial.

Victim co-star Sylvia Syms suggests that Bogarde had the characteristics of one who “loves to watch, to tell dirty stories, but who does not like the messiness, the untidiness of sex”. Not surprisingly, Dirk left the impression of being “a soul in incredible torment”, according to friend and colleague Charlotte Rampling.

Yet Rampling also acknowledges that Dirk “touched happiness sometimes”, and that “Tony was where the happiness came from.”

In fact, another friend and colleague, Faith Brook, described Dirk and Tony’s relationship as “a very perfect marriage”.

There was “a strength of bond”, acknowledges Coldstream, “which united these two men in a relationship that was admired by their friends and by the most casual of acquaintances as more secure than many a marriage. Indeed that word has been used by several of those friends to convey the constancy and the particular air exuded by complementary and equal partners.”

It's good to know that despite all the fear and unhappiness he harboured within, Dirk Bogarde was nevertheless open to experiencing and nurturing a loving relationship with another man - a relationship that for both men was mutually strengthening and sustaining.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

Dirk Bogarde (Part I)

Dirk Bogarde (Part II)

1 comment:

I'm presently reading this bio -- arrived today.

I've read all of Sir

Dirk's books--interesting to find the blank spaces filled in by coldstream. but t hen again-- In postillion-- it's easy to 'read between the lines' when 'they' first met-- bogarde fell in love with tony forwood-- or they both did.

I've seen victim, when I lived in London. very moving.

I do have a huge collection of his films including the Servant.

PS I'm a woman.

Post a Comment