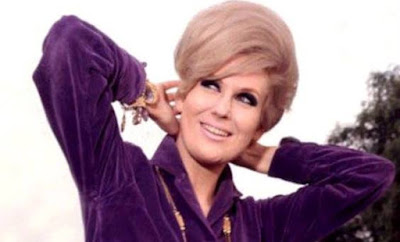

Today marks the 20th anniversary of the death of legendary pop/soul singer Dusty Springfield (1939-1999), widely considered one of the greatest female vocalists of the twentieth century.

My interest in and admiration for Dusty is well documented here at The Wild Reed, most notably in Soul Deep, one of my very first posts. Other previous posts worth investigating, especially if you're new to Dusty, are Dusty Springfield: Queer Icon, which features an excerpt from Laurence Cole's book, Dusty Springfield: In the Middle of Nowhere; Celebrating Dusty (2017), which features an excerpt from Patricia Juliana Smith's insightful article on Dusty's "camp masquerades"; Celebrating Dusty (2013), which features excerpts from Annie J. Randall's book, Dusty!: Queen of the Postmods; and Remembering Dusty, my 2009 tribute to Dusty on the tenth anniversary of her death.

And, of course, off-site there's my website dedicated to Dusty, Woman of Repute (currently only accessible through the Internet archive service, The Way Back Machine).

My website's name is derived from Dusty's 1990 album Reputation, and as I explain in Soul Deep, it was this album that introduced me not only to Dusty's music but also to her life and journey – much of which resonated deeply with me. Indeed, my identification with aspects of Dusty's journey played an important role in my coming out as a gay man.

Above: Stills from the music video for the title track of the 1990 album Reputation. (For my recollections on seeing this video for the first time, click here.)

In honor of Dusty’s life and legacy, I share today (with added images, videos, and links) that part of Trouble Girls: The Rolling Stone Book of Women in Rock that focuses on Dusty. Of course, the problem with a lot of these types of books is that they rigidly group and confine artists into distinct eras. For an artist like Dusty, that's neither accurate nor helpful. Her career, after all, spanned four decades, yet it's often reduced to the 1960s, when she was most prolific. The following excerpt from Trouble Girls, though well-written and insightful, unfortunately does just this. (For a more comprehensive review of Dusty's career, click here and here.)

The one pop singer of the ['60s] era who really had it all – humor and insight, finesse and deep, deep soul – was Dusty Springfield. Born Mary Isabel Catherine Bernadette O'Brien in London, Dusty changed her name around the time she started singing with her brother Tom in a folk trio called The Springfields. By 1963 she had gone solo, and her first hits – "I Only Want to Be With You," "Stay Awhile" – were boisterous, glamorous hip-shakers that threw her in with the British Invasion. Even when she was singing dippy material like "Wishin' and Hopin'" (one of Bacharach-David's rare, tedious gaffs), it was clear that Dusty had an exceptional voice: a low, husky alto that could pick spot-on high notes practically out of thin air. A lot of listeners took her to be black, and the "black" sound of her voice was considered [in Britain, at least] rather exotic at the time.

But there was something else exceptional about her. Try as she might, Dusty just couldn't settle for life as a common pop star. "I don't want to be an entertainer doing a lot of silly things on stage like wearing hats and dancing," she said on the back of Dusty, her second [U.S.] album. In December 1964 she became the first British singer to visit South Africa with an anti-apartheid stipulation in her contract. When she defied regulations and performed in front of a racially mixed audience, the South African government threw her out of the country.

As the sixties wore on, Dusty shed her sweetheart image and began exploring serious emotions. In 1967 she brought a shoulder-to-shoulder intimacy to Bacharach-David's casually sensual "The Look of Love," and tightrope walked the fragile rail of sadness in Randy Newman's "I Think It's Going to Rain Today."

These laid the groundwork for what would be the one true masterpiece of late-sixties female pop singing, Dusty in Memphis. Signed to a new [U.S.] contract with Atlantic, home to Aretha Franklin, Dusty headed south to record with the American Sound Studio's session band and producers Jerry Wexler, Tom Dowd, and Arif Mardin. Instead of forcing a rigid R&B agenda on her, musicians, producers, and singer collaborated in a gorgeous, genre-defying blend of deep soul and orchestral pop. Only the best songs from the best writers were used: Gerry Goffin and Carole King's "I Can't Make It Alone," Newman's "I Don't Want to Hear It Anymore," Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil's, "Just a Little Lovin'." To each of these compositions the American Studio's band added supple backbeats, guitar fills, organ colorations, and bass lines that were never obvious, but always securely felt. On top of all of that, Dusty sung like an angel. Her phrasing were plaintively expressive yet technically astounding, and she delivered each line with tender abandon. She made exquisite use of her upper register, finding a vast repertory of shadings in her falsetto range. There's not a hard note sung or played on the album.

Dusty in Memphis wasn't a huge hit at the time, although its single, "Son-of-a-Preacher Man" did go to Number Ten. Perhaps audiences just weren't expecting serious art from a beehived, overly eye-shadowed British girl singing deep soul music against a Southern band's backdrop. More to the point, they weren't expecting it from the fluffy female pop genre. Dusty was singing about some of the most difficult and intimate female emotions – loneliness, shame, vulnerability, the inability to survive without a man's validation – and she brought to them a conviction that has seldom been managed by any female singer, except maybe Billie Holiday.

Dusty didn't put a cute happy face on heartbreak or dress it up in snazzy high-heeled boots, she confronted it for the messy, self-annihilating trauma it really is. In "I Don't Want to Hear It Anymore," the singer learns of her lover's unfaithfulness from cheap neighborhood gossip. In "Breakfast in Bed," she's playing the other woman herself – an unfaithful lover is better than no lover at all. By the last song, she's literally breaking down, begging a lover to take her back. Who else can I turn to? she sings, Oh baby, I'm begging you / Won't you reach out for my dying soul / And let me live again?

Today, Dusty in Memphis is regarded as a classic, although it still remains something of a cult favorite. It's rarely mentioned in its proper context: alongside albums like the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, Van Morrison's Astral Weeks, Neil Young's Tonight's the Night, and other great treatises of emotional disarray. People think that because Dusty didn't write her own songs or play her own instrument she doesn't deserve equal credit for her work. But she does. She lived every broken minute.

– Excerpted from Trouble Girls:

The Rolling Stone Book of Women in Rock

Edited by Barbara O'Dair

Random House, 1997

The Rolling Stone Book of Women in Rock

Edited by Barbara O'Dair

Random House, 1997

Related Off-site Link:

Dusty Springfield 20 Years On: Remembering the British Soul Star Who Defined a Decade – Joe Sommerlad (The Independent, March 2, 2019).

For more of Dusty at The Wild Reed, see:

• Soul Deep

• Soul Deep• Celebrating Dusty (2017)

• Celebrating Dusty (2013)

• Dusty Springfield: Queer Icon

• Remembering Dusty (2018)

• Remembering Dusty (2009)

• Remembering Dusty – 11 Years On

• Remembering Dusty – 14 Years On

• The Other "Born This Way"

• Time and the River

• Remembering a Great Soul Singer

• A Song and Challenge for 2012

• The Sound of Two Decades Colliding

Opening collage: Michael J. Bayly (1992).

Closing images: At Dusty's grave at St. Mary the Virgin Churchyard, Henley-on-Thames, England – Sunday, August 21, 2005.

4 comments:

Thanks, Michael. This is a fantastic tribute to Dusty.

Brilliant tribute, Michael, and some great pics!

Great read, Michael!

Awesome tribute. Thanks

Post a Comment