My sister-in-law recently lent me a VHS copy of Norman Jewison’s 1973 cinematic interpretation of Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice’s “rock opera”, Jesus Christ Superstar.

My sister-in-law recently lent me a VHS copy of Norman Jewison’s 1973 cinematic interpretation of Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice’s “rock opera”, Jesus Christ Superstar.I watched it last night and, as always, was quite moved by many aspects of it. The song “Could We Start Again, Please,” for instance, can still bring a tear to my eyes!

Jewison’s use of the Israeli desert locations is phenomenal. And, of course, those groovy 1970s’outfits and hairdos are really something! In fact, I’ve always thought that because the sound of this musical is so reflective of the early ‘70s, any production of it that fails to somehow have the look of this era comes across as deficient.

It was also interesting to watch the film for the first time in over ten years, and realize that during that time I’ve dated a guy who looks like Bob Bingham, the actor who plays the High Priest, Caiaphas – though minus the bushy beard and baritone singing voice! (Plus, Caiaphas must have one of the best lines in the film: “One thing I’ll say for him, Jesus is cool.”)

Of course, I find certain aspects of Jesus Christ Superstar problematic. For a start, the film perpetuates the fallacy that Mary of Magdala was a prostitute.

It also reinforces the anti-Semitism of much of the New Testament by erroneously placing the bulk of the blame for Jesus’ torture and execution on the Jews rather than the Romans, as the following song from the film clearly demonstrates.

Let’s be clear: Jesus’ death was not primarily a result of his falling out with the religious authorities of his day. If this had been the case, then the Jewish religious leaders could simply have had him stoned to death, without having to consult the Roman authorities. Contrary to what Caiaphas says to Pilate in Jesus Christ Superstar, the Jews did indeed have their own “laws to put a man to death.”

Yet Jesus wasn't stoned to death, he was crucified, and crucifixion was the Roman method of execution for those considered to be political and social agitators.

Furthermore, any depiction of the life of Jesus of Nazareth that makes Judas a more compelling and sympathetic character than Jesus himself, has missed the boat.

Judas, electrifyingly portrayed by the late Carl Anderson (right), also gets the most visually (and symbolically) intriguing scenes (like the one in which he is being pursued across the desert by modern-day tanks!)

He also gets the best songs. One of these is the opening number, “Heaven On Their Minds” (see below) – a number which, from the get-go, brings into impressive focus all the best elements of Jewison’s film – location, costumes, performances, and the passion and political intrigue inherent to any story that pits a message of egalitarianism and liberation against the oppressive and dehumanizing might of imperial power.

Anderson’s performance is a show-stopper – and remember this is the first song! His portrayal of the despairing and ultimately frightened Judas, desperately attempting to warn Jesus of the wrath of the occupying Romans, is both mesmerizing and heartbreaking. Just listen to the despair in his voice when, towards the end of the song, Judas laments, “He won’t listen to me.”

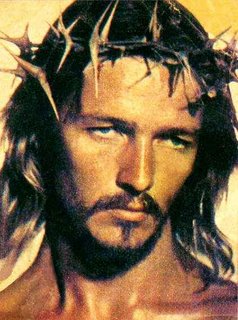

Without doubt, Judas is a well-developed and sympathetically-drawn character in Jesus Christ Superstar. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about Jesus, played in the film by Ted Neeley.

In Jesus Christ Superstar, Jesus is depicted as an “innocent puppet,” a hapless player in a vast cosmic game in which he has no hand in calling the shots, as “everything is fixed” and thus nothing can be changed. He is a tool to be used in some grand design not of his making.

Notions of a violent God

Of course, such an understanding isn’t that far removed from the orthodox view of Jesus’ death, for as my friend Jack Nelson-Pallmeyer notes in his latest book, Is Religion Killing Us? Violence in the Bible and the Quran, “many Christians [believe in] a gracious God who loves us enough to send his only son to die in our place so that we might avoid punishment, go to heaven instead of hell, and have eternal life.”

Yet such a “rose-colored” interpretation, insists Nelson-Pallmeyer, conceals “brutal images of God.”

“If we believe that Jesus died for us so that we will not be condemned,” says Nelson-Pallmeyer, “then we should ask, ‘Condemned by whom?’ The answer is, God. What remains unstated in classic Christian statements of faith is that Jesus dies in order to save us from God, not from sin. More precisely, Jesus’ sacrificial death saves us from a violent God who punishes sin.”

“The idea that God sent Jesus to die for our sins makes sense only if we embrace violent and punishing images of God featured prominently in the Hebrew Scriptures,” concludes Nelson-Pallmeyer. Like the writers of the Hebrew Scriptures, many of the New Testament writers project abusive, violent power onto God.

Why did Jesus die?

So, if we reject the notion that Jesus was predestined to die for the sins of humanity, why then did he die? And what is the significance of his death for those of us who claim to be his followers?

Well, I always like to say that it isn’t so much Jesus’ death that saves, but rather his life – a life which, of course, led to his eventual death at the hands of those heavily invested in a system of dominating imperial power; a hegemonic power, willing to do whatever it takes to stay in control. Sound familiar?

Theologian Daniel Helminiak, in writing about Jesus as a “model for coming out,” suggests that, “Jesus did not know precisely where his life was leading and what the exact outcome would be – although, as circumstances unfolded, it would not have taken a rocket scientist to figure it out, and toward the end he must have realized that his sense of authority was on a collision course with the authorities [of the hegemonic power of his day].”

And yet Jesus persisted in preaching and living his message of God’s inclusive love and radical hospitality.

I’ve come to believe that it was for this message that Jesus ultimately died. Indeed, Jesus believed in it so much that not even the prospect of torture and death could deter him from imparting the liberating message of both God’s love and humanity’s potential to be, like him, living embodiments of this transforming love.

Helminiak reflects a similar view when he writes that, “Jesus’ death was redeeming only insofar as it was the ultimate expression of his human virtue. Precisely his virtue restores human commitment to, and trust in, God. Jesus’ human fidelity – first to himself and thereby to God, from whom he came – is what reconciles humankind with God. [ . . .] The self-affirmation of this wondrous human being, even in the face of death, is Jesus’ saving contribution.”

“The lesson of Jesus is a lesson about human living,” says Helminiak. “The lesson is that fulfillment in life must come from our being ourselves. [. . .] As Jesus' experience shows, we know God and God’s will only in probing our own hearts; we will be true to God by being true to our deepest and best selves.”

Affirming such an understanding of Jesus’ life and death allows Helminiak to echo the perspective of Nelson-Pallmeyer: “Away with other notions”, says Helminiak, “for example, that God intended Jesus’ gruesome murder [. . . ] or that in justice God demanded Jesus’ blood, or that Jesus was born precisely to die in sacrifice for others, or that Jesus’ painful death was the price paid to God for sin! These notions [. . .] make God out to be an ogre. They are also bad psychology: They encourage unhealthy attitudes” . . . as attested by centuries of religious imperialism, “holy” wars, inquisitions, and persecution of anyone whose experiences take them beyond the parameters of orthodoxy.

It’s enough to make you ask, “Could we start again, please?”

See also the related Wild Reed posts:

• Why Jesus Is My Man

• Judas and Peter

• Jesus: Our Guide to Mystical Love in Action

• Jesus and Social Revolution

• The "Incident" in the Temple

• Blaming the Jews, Canonizing Pilate

• "I've Been Changed; Yes, Really Changed"

• Mary of Magdala

• Mary Magdalene – "An Icon for Our Century"

• A Prayer on the Feast of Mary Magdalene

• The Sexuality of Jesus

• Reflections on The Da Vinci Code Controversy

• Thoughts on The Da Vinci Code

• Jesus Was a Sissy

• Christianity and the Question of God's Presence in the Midst of Hardships and Heartache

• Discerning and Embodying Sacred Presence in Times of Violence and Strife

• Resisting the Hand of the Empire

• Carl Anderson: “Still One of the Greatest Interpretations of Judas on Film”

• Carl Anderson’s Judas in Jesus Christ Superstar: “The Gold Standard”

• Carl Anderson’s Judas: “A Two-Dimensional Popular Villain Turned Into a Complex Human Being”

No comments:

Post a Comment