.

Tonight for "music night" at The Wild Reed I share the video for D’Angelo’s 2000 single, “Untitled (How Does It Feel?),” a track from his groundbreaking album, Voodoo, released 20 years ago yesterday. I also share a number of insightful perspectives on this “subversive” and thus, for some, controversial video.

But first, NPR music critic Sam Sanders recently interviewed recording engineer Russell Elevado on the making of Voodoo. In introducing this interview, Sanders says the following about the album.

While many today think of it as a masterpiece, it seems we still haven't figured out how to make sense of Voodoo: what box to place it in, how to pay it the respect it deserves, all the nuance and depth of a young black artist making a previous generation’s black music.

Voodoo is so many things. It is jazz, soul and funk all at once. You can hear hip-hop’s footprint in some of the songs, but it never dominates. While the influence of Prince and Funkadelic and Marvin Gaye is there on every track, it draws just as much inspiration from Hendrix and The Beatles. And for the artist, it was such an important statement that he waited nearly 15 years to follow it up. If it took time to see that Voodoo didn't live in the same music world as its peers in 2000, by now it has stopped feeling vintage – and started feeling timeless.

. . . [I]f you'll have me

I can provide everything that you desire

Said if you get a feeling

Feeling that I am feeling

Won't you come closer to me, baby

You've already got me right where you want me, baby

I just want to be your man

How does it feel

How does it feel

Said I want to know how does it feel

Writes Elijah C. Watson on D’Angelo’s “subversive” video for “Untitled (How Does It Feel?)”:

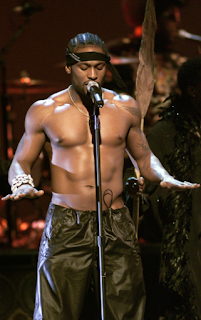

For most of the four-and-a-half minute-long video – which was directed by Paul Hunter and Dominique Trenier – D’Angelo’s upper body is the focus. The camera expands from his black braids, brown eyes, and his plump, licked lips, to show a glistening and chiseled chest and V-cut abs, the screen cut off right at the point of his waist to where a viewer can’t help but wonder if he’s nude or not. There’s nowhere to avert your eyes as the one-shot video offers a voyeuristic exploration of D’Angelo’s body. It’s intimate, provocative, sensual, vulnerable – a hypnotizing performance that offers no relief until its over, beautifully capturing the pleasures of sex without being explicitly overt.

The video is subversive, a display of black masculinity that’s affectionate but confident, and delicate but strong. A middle ground between Tupac’s infamous bathtub photos and the first 30 seconds of Prince’s “When Doves Cry” music video.

“Untitled” was distinct from other hip-hop, R&B, and pop videos because of this. Unlike the hedonism and hypermasculinity found in hip-hop and R&B videos or the teenage-like fantasies found in pop videos, “Untitled” felt real and offered a display of blackness uncommon in music videos at the time.

Luis Minvielle also insightfully weighs-in on the significance and uniqueness of both the music video for “Untitled (How Does It Feel?)” and Voodoo overall, suggesting that both “laid out the blueprint for a new masculinity.”

The [album’s] resolve of exploring love was forthright: its liner notes, written by poet Saul Williams, poised Voodoo as an hour-long ceremony expected to “serenade darkness.” “We speak of darkness as the unknown and the mysteries of the unseen,” the sleeve read. If romance was something unfamiliar to the listener, then Voodoo was the gateway into the mystique surrounding the different stages of human intimacy.

. . . [F]or all its noteworthy features, Voodoo is best remembered for D’Angelo’s sexy appearance – naked and sly – in the music video for “Untitled (How Does it Feel?).” In it, a smoldering D’Angelo sings and flexes past the swooning point, the grooves in his body running as deep as the low-end bass in Voodoo’s central tracks. One can fathom why memories of Voodoo are mostly associated with his strikingly alluring chest rather than the messages of love or his devoted rendition of soul music. It was all about exposition – nothing else from the record had as much airtime and as much attention as the video for “Untitled.” It was Voodoo’s driver for success. D’Angelo became a sex symbol, an icon for black macho bravado and suggestive lovemaking invitations and, naturally, a superstar. . . . [Yet] this attention was too much for a sensitive soul. The shy son of a Pentecostal preacher, D’Angelo could never cope with being a superstar. To his dismay, he was acclaimed for his body and not for his music. After touring for Voodoo, D’Angelo disappeared from the public eye. He rarely showed up, and when he did, music was the last issue to touch upon: he was caught up in a mugshot in 2005, overweight and frightened. It would be another 14 years before he would release Voodoo’s follow up, the future-funk protest album Black Messiah.

. . . Twenty years later, there’s still ground to break from one of neo-soul’s masterpieces: no other record has since portrayed sexuality in a way so appealing, yet so respectful. This achievement, concealed behind beautiful bodies and superstar narratives, has been Voodoo’s defining triumph: the inclusive representation of all sides of intimacy, love, sex and romance by embracing the feminine. D’Angelo was able to create this state of expression, of inclusive intimacy and universal love, by embracing his own femininity, and embracing what’s feminine in soul music. The liner notes are exact: “If we are to exist as men in this new world many of us must learn to embrace and nurture that which is feminine with all of our hearts.” . . . Contrary to the barbaric G-Funk tropes that swamped hip-hop, Voodoo understood that reclaiming femininity did not mean shunning masculine aspects of sexuality. While turn-of-the-century emcees would gloat in misogyny to explain arousal, Voodoo portrayed sexuality as both steamy and sympathetic. As the artwork implies, Voodoo’s posture is a posture of contemplation.

And finally, here’s more about both “Untitled (How Does It Feel?)” and its parent album Voodoo, courtesy of Wikipedia (here and here):

Voodoo is the second studio album by American neo soul singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist D’Angelo. It was released on January 25, 2000, by Virgin Records.

D’Angelo recorded the album during 1998 and 1999 at Electric Lady Studios in New York City, with an extensive line-up of musicians associated with the Soulquarians musical collective. Produced primarily by the singer, Voodoo features a loose, groove-based funk sound and serves as a departure from the more conventional song structure of his debut album, Brown Sugar (1995). Its lyrics explore themes of spirituality, love, sexuality, maturation, and fatherhood.

Following heavy promotion and public anticipation, the album was met with commercial and critical success. It debuted at number one on the US Billboard 200, selling 320,000 copies in its first week, and spent 33 weeks on the chart. It was promoted with five singles, including the hit single “Untitled (How Does It Feel?),” which was written and produced by D’Angelo and Raphael Saadiq, and originally composed as a tribute to musician Prince. The song’s lyrics concern a man’s plea to his lover for sex.

The music video for "Untitled (How Does It Feel?)" garnered D’Angelo mainstream attention and controversy. Directed by Paul Hunter and Dominique Trenier, the video consists entirely of one shot featuring a muscular D’Angelo appearing nude and lip-synching to the track. While initial reaction from viewers was divided with praise for its sexuality and accusations of sexual objectification, the video received considerable airplay on music video networks such as MTV and BET, and it helped increase mainstream notice of D’Angelo and Voodoo. It also helped engender an image of him as a sex icon to a younger generation of fans.

D’Angelo promoted Voodoo with an international supporting tour in late 2000. While successful early on, the tour became plagued by concert cancellations and D’Angelo’s personal frustrations. The singer’s portrayal as a sex symbol in “Untitled (How Does It Feel?)” had repercussions on the tour, with female fans yelling out for him to take his clothes off and tossing clothes onto the stage. As trumpeter Roy Hargrove recounted, “We couldn’t get through one song before women would start to scream for him to take off something [...] It wasn’t about the music. All they wanted him to do was take off his clothes.” This led to frustration and both onstage and offstage outbursts by D’Angelo. Music journalist Questlove later said, “He’d get angry and start breaking shit. The audience thinking, 'Fuck your art, I wanna see your ass!', made him angry.” Although some were cancelled due to D’Angelo’s throat infection during the tour’s mid-March dates, many shows were cancelled due to his personal and emotional problems.

D’Angelo’s discontent with his sex symbol image led to his period of absence from the music scene following the conclusion of Voodoo's supporting tour.

“Untitled (How Does It Feel?)” won a Grammy Award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance at the 43rd Grammy Awards in 2001. Rolling Stone magazine named the song the fourth best single of 2000. The magazine later named it the fifty-first best song of the 2000s (decade).

Upon its release, Voodoo received general acclaim from music critics and earned D’Angelo several accolades. It was named one of the year’s best albums by numerous publications.

Voodoo has since been regarded by music writers as a creative milestone of the neo soul genre during its apex. It has sold over 1.7 million copies in the United States and has been certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

Soul Legend D'Angelo, 51, Dies After

Private Battle with Pancreatic Cancer

– Ilana Kaplan and Janine Rubenstein

People Magazine

Related Off-site Links:

D’Angelo’s Voodoo Redefined What an R&B Album Could Be – Kristin Corry (VICE, January 24,2020).

D'Angelo: Voodoo Child – Paper (December 1, 1999).

There Will Never Be Another Music Video Like D’Angelo’s “Untitled (How Does It Feel?)” – Elijah C. Watson (OkayPlayer, January 23,2020).

D’Angelo’s Masterpiece Voodoo Laid Out the Blueprint for a New Masculinity – Luis Minvielle (OkayPlayer, January 23,2020).

The New D’Angelo Documentary Shows a Musician Tired of Being a Sex Symbol – Kristen Yoonsoo Kim (Pitchfork, April 30, 2019).

For Everyone Who Had a Sexual Awakening Watching D’Angelo’s “Untitled” Video – Sylvia Obell (BuzzFeed, September 30,2016).

D’Angelo’s Black Messiah Is Political, Personal and Necessary – Mikey IQ Jones (Fact, December 18,2014).

The Second Coming of D’Angelo – Brian Hiatt (Rolling Stone, June 15, 2015).

Second Coming: D’Angelo’s Triumphant Return – Sasha Frere-Jones (The New Yorker, January 5, 2015).

D’Angelo’s Black Messiah Was Worth Waiting 15 Years For – James Joiner (The Daily Beast, December 16, 2014).

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• A Fresh Take on Masculinity

• Learning from the East

• Engelbert Humperdinck: Not That Easy to Forget

• Celebrating Al Green, Soul Legend

• Carl Anderson: “Like a Song in the Night”

• Changes

• Rockin’ with Maxwell

• Maxwell’s Hidden Gem

• Maxwell in Concert

• Maxwell’s Welcome Return

• Lenny

• State of Grace

• Remembering Prince, “Fabulous Freak, Defiant Outsider, Dark Dandy” – 1958-2016

• Ocean Trip

• Donald Glover: Renaissance Man

• Quote of the Day – May 8, 2018

• Deconstructing Childish Gambino's “This Is America”

• In a Historic First, Country Music's Latest Star Is a Queer Black Man

Previously featured musicians at The Wild Reed:

Dusty Springfield | David Bowie | Kate Bush | Maxwell | Buffy Sainte-Marie | Prince | Frank Ocean | Maria Callas | Loreena McKennitt | Rosanne Cash | Petula Clark | Wendy Matthews | Darren Hayes | Jenny Morris | Gil Scott-Heron | Shirley Bassey | Rufus Wainwright | Kiki Dee | Suede | Marianne Faithfull | Dionne Warwick | Seal | Sam Sparro | Wanda Jackson | Engelbert Humperdinck | Pink Floyd | Carl Anderson | The Church | Enrique Iglesias | Yvonne Elliman | Lenny Kravitz | Helen Reddy | Stephen Gately | Judith Durham | Nat King Cole | Emmylou Harris | Bobbie Gentry | Russell Elliot | BØRNS | Hozier | Enigma | Moby (featuring the Banks Brothers) | Cat Stevens | Chrissy Amphlett | Jon Stevens | Nada Surf | Tom Goss (featuring Matt Alber) | Autoheart | Scissor Sisters | Mavis Staples | Claude Chalhoub | Cass Elliot | Duffy | The Cruel Sea | Wall of Voodoo | Loretta Lynn and Jack White | Foo Fighters | 1927 | Kate Ceberano | Tee Set | Joan Baez | Wet, Wet, Wet | Stephen “Tin Tin” Duffy | Fleetwood Mac | Jane Clifton | Australian Crawl | Pet Shop Boys | Marty Rhone | Josef Salvat | Kiki Dee and Carmelo Luggeri | Aquilo | The Breeders | Tony Enos | Tupac Shakur | Nakhane Touré | Al Green | Donald Glover/Childish Gambino | Josh Garrels | Stromae | Damiyr Shuford | Vaudou Game | Yotha Yindi and The Treaty Project | Lil Nas X | Daby Touré | Sheku Kanneh-Mason | Susan Boyle

No comments:

Post a Comment